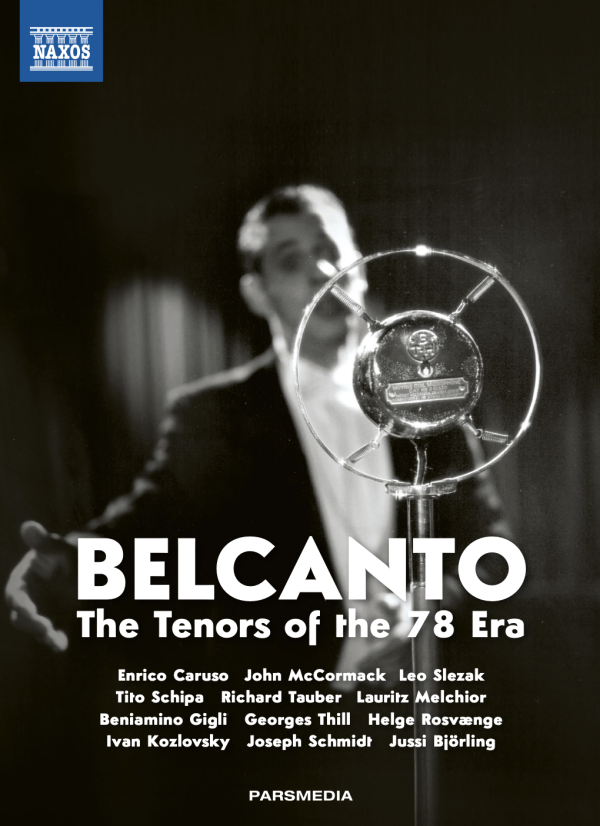

Belcanto – The Tenors of the 78 Era

Facts

Music Documentary Series, 13 x 30 min + 2 x 60, 2017Directed by Jan Schmidt-Garre

With the development of sound film in the 1920s and 30s, the great tenors, such as Beniamino Gigli, Richard Tauber and Lauritz Melchior, became movie stars. Countless “singer movies” were made, but great vocal performances were also captured in documentaries and privately made movies. Using a wealth of rare restored material, this thirteen-part documentary series presents the great tenors from Enrico Caruso to Iussi Björling and, together with vivid accounts by contemporary witnesses and profound analyses by experts – above all Jürgen Kesting – it offers a deep and inspiring insight into the art of bel canto.

A two-hour version features highlights of the series from the director’s personal perspective.

Belcanto – The Tenors of the 78 Era was broadcast in thirty countries and won several awards.

Episodes:

Enrico Caruso (1873–1921)

John McCormack (1884–1945)

Leo Slezak (1873–1946)

Tito Schipa (1889–1965)

Richard Tauber (1891–1948)

Lauritz Melchior (1890–1973)

Beniamino Gigli (1890–1957)

Georges Thill (1897–1984)

Helge Rosvænge (1897–1972)

Ivan Kozlovsky (1900–1993)

Joseph Schmidt (1904–1942)

Iussi Björling (1911–1960)

Dialogue with Eternity

Cinematography: Wolfgang Aichholzer, Pascal Hoffmann

Editor: Gaby Kull-Neujahr

A co-production with ZDF/3sat and Naxos Audiovisual

Supported by the Bavarian Film Fund FFF

Awards

Columbus International Film Festival

Classique en images

ICMA Award

Releases

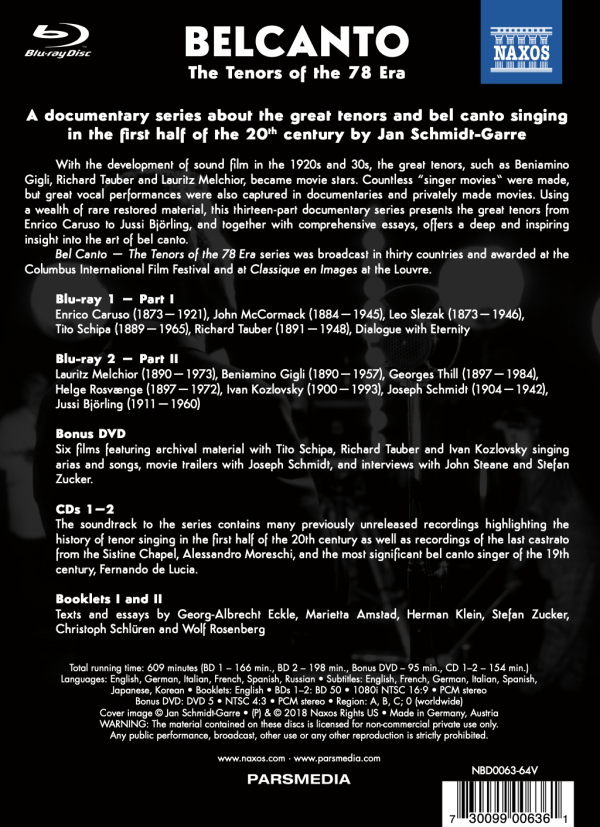

On Bluray and DVD with Naxos Audiovisual including many video and audio bonus tracks and a comprehensive book on the art of singing:

Protagonists

Björling • Kozlovsky • Schmidt • Rosvaenge • Gigli • Thill • Schipa • McCormack • Slezak • Melchior • Tauber • Dialogue with Eternity • Caruso

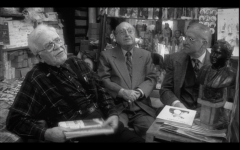

Björling

scene:

A gathering of Iussi Björling’s former colleagues at the Café of the Stockholm Opera, where Björling gave 642 performances. Collaboration with Björling was the pivotal influence on their musical development.

music:

Meyerbeer, Verdi, Puccini, Bizet, Schubert, Nordqvist

analysis: Ingemisco (Messa da requiem, Verdi), 1939

Quotes from the film’s exposition...

I cannot think of any other voice than Björling’s that was better placed, more exactly focused or better centered. (Kesting) Standing next to him, you adapted the same way of breathing: this fantastic, natural way of singing that he had. You really sang better than you had done in all your life. (Söderström)

...from its development...

David, my grandfather, started to teach him singing right at the beginning. My father had his first lessons at the age of four. When the fourth son was born, Carl, their mother died and David was left alone with his boys. Those were difficult times and they started to give concerts and were very successful. (Lars Björling) I remember a jubilee concert with Jussi. In the middle of the encore he said: "Come on, let’s go back-stage and drink a whisky!" He took me with him to the box, and everybody thought he was leaving because the jubilee concert had moved him. The audience clapped and cheered like mad. Jussi said to me: "Come on, let’s start again from the beginning." Everything had happened, and I was the only one who knew what we had done during this interval. (Bokstedt)

...and from its resolution

Jussi Björling’s character was so Swedish: hering and young potatoes and dill and linguan silt and bright nights. Jenny Lind tried to describe her voice and the Swedish voices. "Our voices are an imagination of the bright nights in June. They have a scent of pinetrees." (Söderström) I regard him as the classical tenor after Caruso. (Kesting) It was an honour to work with him. It was the best thing I could have imagined in my life. Never forget it – just be grateful, very grateful. (Bokstedt)

Kozlovsky

scene:

The New Virgin Convent in Moscow. Ivan Kozlovsky’s grand-daughter Anna meets Svetlana Sobinova, the daughter of Kozlovsky’s great predecessor at the Bolshoi Theatre, Leonid Sobinov.

music:

Wagner, Rachmaninow, Tchaikovsky, Verdi, Lyssenko, Mussorgsky, Ukrainian folk-songs

analysis: È il sol dell’anima (Rigoletto, Verdi), ca. 1948

Exposition...

There are plenty of good singers. There are far few singers who are also good actors. But good singers who are also good actors and artists – they are very rare indeed. Only one is born every hundred years. Kozlovsky was first and foremost an artist. (Pitchugin)

...confrontation...

Many of singers in the role of Lensky screamed out the sentence: "You are an unprincipled seducer!" Lensky was an aristocrat, though. Kozlovsky whispered these words. But they could still hear this whisper back in the fifth row of the Bolshoy Theatre because the whole audience lived the role with him. Kozlovsky kept to the principle: "The more you scream the less you sing." (Malakhova) More than any other tenor in this century, he followed on from Fernando De Lucia. He maintained the bel canto tradition in certain formal elements. He used long diminuendi, he used the messa di voce, the upward and downward swelling of the voice. The residual effect of the bel canto school apparently survived in the Tsarist court theatre long after it had ceased to exist in Italy. (Kesting) I don’t know what Kozlovsky thought of Stalin. I once saw a certificate on the wall in his home. In it, Stalin thanked Kozlovsky very much for donating a big sum of money for the construction of an army tank. It was signed: I. Stalin. (Pitchugin) Stalin once said to him: "You can ask for anything you want from me. But I will not allow you to travel abroad." (Pitchugin)

...resolution

He departed this life on 21st December 1993. He gave great light, and now his light is extinguished. May his name be praised. From the chalice of life he drank immortality. (Baboreko) If I have anything good in me, even just a little goodness, I mainly have Kozlovsky to thank for it. Nothing raises and enhances the spirit so much as music and singing. (Pitchugin)

Schmidt

scene:

New West End Synagogue in London. Cantor Alan Bilgora demonstrates the technique of florid singing that Joseph Schmidt learned as a young cantor.

music:

Meyerbeer, Buzzi-Peccia, Flotow, Halévy, Tagliaferri, songs, an Aramaic prayer

analysis: Recha, als Gott dich einst (La Juive, Halévy), 1931

Quotes from the film’s exposition...

From a technical point of view Schmidt’s voice is very difficult to analyze, because it is by nature a voice that didn’t have problems, where most tenors do. (Bilgora) It was one of these voices which bore a touch of death, and suffering. It contained an inner complaint. (Kesting) He was so kind-hearted, it made you want to put your arms round him and comfort him. Although he never cried. (Lindbergh-Salomon)

...from its development...

The synagogue tradition preserved florid singing into the 1950’s and 60’s. Just as Yiddish embodies – to a degree – medieval German, so orthodox cantorial practice embodies certain things that were done in the opera houses in the 18th and early 19th centuries. So, Schmidt is giving us a glimpse of the kind of florid singing that florished in Italy in Rossini’s day. (Zucker) There is a wonderful quotation from Schubert: "I do not know any cheerful music". Joseph Schmidt sometimes sings happy, carefree attractive, charming songs but never any "cheerful music". (Kesting) On April 1st 1933 Hitler’s regime made it impossible for Schmidt to continue because of a law banning Jews from working for the government. He returned to Berlin in connection with the opening of his film “Ein Lied geht um die Welt”. Goebbels was in the audience. So enthusiastic was he, that he wanted to declare Schmidt an honorary Arian. Much of the rest of Schmidt’s life involved flight from the Nazis. (Zucker)

...and from its resolution

One has to grow so very old with all these memories. Just imagine. It’s comical, isn’t it? Almost comical. (Lindbergh-Salomon)

Rosvaenge

scene:

A family party at the Rosvænge’s house near Copenhagen. Even though Rosvænge spent his formative years in Berlin and Vienna, he regarded himself throughout his life as a Dane.

music:

Meyerbeer, Puccini, Hugo Wolf, Beethoven, Leoncavallo, (Rosvænge), Wagner (Max Lorenz)

analysis: Der Feuerreiter (Hugo Wolf), 1938

Exposition...

When you saw him, you forgot you were in the theatre. It sometimes made your hair stand on end. (Luther) Rosvænge is always particularly good in the very roles that do not demand decoration, or ornamentation, or a singer’s elegance or subtlety. He could present a figure boldly, straightforwardly, rhetorically. (Kesting)

...confrontation...

In Berlin and Dresden at about this time, Fritz Busch, Leo Blech, and others had already started the so-called German Verdi Renaissance. Fritz Busch brought the fiery, dramatic espressivo style to Germany which Toscanini had developed. Helge Rosvænge’s voice qualities made him the ideal protagonist of this style. (Kesting) He was enormously economical in breathing. He could sing a very long phrase without using much breath. The art lies not in breathing but in breathing out. (Gougaloff) You see someone in the street you haven’t seen for ages. "Hi!" – that's enough for a whole phrase. You don’t have to breath any more than that. Too much breath has to come out, and it spoils your note. The note must come out on its own. (Luther) Most of Rosvænge’s potential lay in the declamato and not in the agreeable cantabile of Italian singing. He had a kind of flaming energy. His espressivo was part of the theatrical diction of those years. Perhaps it was also the diction of politics. This could have been the origin or the basis. (Kesting)

...resolution

I can hear a hero who is really broken. I think this is brilliantly presented by the breathing, by the great opening of the note, immediately dropped again. I have never heard any other singer who could do this. (Eckle) And with the change-over to more declamatory singing. (Fischer) It provided a lesson to Fischer-Dieskau and Gerhard Hüsch. Incredibly, it leads to a new form of aesthetics. (Eckle) Getting away from the “heroic tenor”. (Fischer) And getting away from singing as such. (Eckle) As Mahler said: "All singing is over." (Fischer)

Gigli

scene:

A wine festival in Recanati, the town in which Beniamino Gigli was born. The regular guests in a bar are discussing Gigli, who over the course of his career continually returned to give benefit concerts in his home town.

music:

Meyerbeer, Mascagni, Zandonai, Puccini, songs

analysis: Apri la tua finestra (Iris, Mascagni), 1921

Exposition...

When I hear him sing, I am filled by a special feeling. A cold chill goes down my back. We call it “goose-pimples”. (Pagliarini) When you hear records of the very young Gigli you hear the genuine, original Italian tenore di grazia. It is a very soft, gentle voice, totally pure and clear. It does not have the fullness and energy of Caruso's voice but it is called in Italian dolcezza – very sweet, but not sweetish. (Kesting)

...confrontation...

I sang for Hitler. I sang a concert with my father and then Hitler received me and my father and complimented us very much. We didn’t really have anything to do with that. (Rina Gigli) The accusations made against Gigli came from Anglo-Saxon critics and from a few German critics. The Germans were perhaps criticising an under-tone which could have been heard in the 1930s and 1940s not only in artistic performances but also in political speeches. Flattering, giving orders, complaining, shouting, exaltation. All the elements you can hear in the political spectrum from Goebbels and Hitler to Mussolini. Gigli is a fascinating example of the impression made by the political currents of the day on artistic performances. (Kesting) He had a fabulous voice, and a natural gift. But he did not have very much taste. He tended to imitate Caruso. He sobbed, because Caruso had tears in his voice. In Gigli's case, the tears were rather artificial. (Celletti) The sobs flowed out of his response to words and music and they did not disrupt the music’s flow. He integrated the sobbing into the dynamic curve of the phrases. (Zucker) It helped to breathe, in order to bring the phrase to an end. It was a technical trick which he used as means of expression. I liked it. (Simionato)

...resolution

I have sung so close to him, for instance in the “Dream” scene in Manon. It was magnificent, to follow his notes from so close up. These pianissimi, which rise on the breath. It was a great pleasure for me because I could hear how well he breathed. The lovely, gentle notes – his technique was fantastic. (Olivero) Even if he did not have a particularly dark voice he could still do everything with it. He used it in whichever way he wanted. You realize that I’m an admirer of Gigli, don’t you? (Cerquetti)

Thill

scene:

A wine-growing estate in Lorgues in the South of France. After the early conclusion of his career Georges Thill retired to Provence, where his wife still lives, to teach and grow wine.

music:

Meyerbeer, Charpentier, Wagner, Gounod, Canteloube, Chansons

analysis: Salut, demeure (Faust, Gounod), 1930

Exposition...

He had taken a noble singing style from the tradition of De Lucia but became a very puristic, linear singer. He was a contemporary of Toscanini and had adopted the same strict style which gripped all Europe at the time. (Kesting) Georges Thill was a painter in singing. When you hear him, you realize that voice production gave him sensual pleasure. He colours the vowels like a gourmet who can identify each kind of fruit, fish, or vintage wine. (Reiss)

...confrontation...

Georges Thill was an extraordinary vocal technician. He had developed his voice and morphology to perfection. A singer’s morphology is very important. Most singers have a very broad face, and plenty of space for resonance. (Reiss) I would not condemn anyone to a tenor’s life! One feels happy if one has given pleasure to the audience. Then you can say to yourself: "I’ve made it!" But getting there is misery! Your digestion is ruined, you can never sleep. It is either too hot or too cold. Exhaustion from beginning to end. De Lucia said: "You are only good once a year." (Georges Thill, 1977) When an Italian sings “amore” he can stretch the “o” out for ever and the “r” is only a tiny bridge leading to the “e”. If I sing “chaste et pure” in French I must form a number of consonants perfectly and then I cannot create so much tonal pressure. I therefore have to sing everything more lightly. (Kesting)

...resolution

He will always be the greatest example of a French tenor and of the interpretation of the French repertoire. But he is a regional product like crêpes or marmelade or olive oil. (Reiss)

Schipa

scene:

A gathering of Tito Schipa’s colleagues in the Café Tortoni in Buenos Aires. As a Southern Italian, Schipa had a particular affinity to spanish culture and music and considered the Teatro Colon as his second home.

music:

Puccini, Padilla, Flotow, Tosti, Massenet, Donizetti, Tangos

analysis: Ah! Non mi ridestar (Werther, Massenet), 1925

Exposition...

He had a way of phrasing and a fabulous diction. He sang like an open book. You could understand everything. (Pasini) His voice is like a ray of sunshine penetrating the mist. As the sun rises, the rays shine through more strongly. (Kesting)

...confrontation...

Schipa’s small voice was big enough to fill an auditorium like the Teatro Colon, which seats 3,500 to 4,000 people. Even his pianissimi were a gentle whisper which reached the whole theatre. (Turro) For him, singing was a form of conversation. He said the music. (Zucker) The note floats away. It is like breathing out but almost without losing any air. The singer makes a fiato – draws breath only for an instant. The amount of air does not matter. He has to convert all the air he has breathed in into sound. (Kesting) As a young man he had been very good-looking. I think he was the best-looking of all the tenors. The ladies of course worshipped him. They all flocked to him. (Brodsky) So great was his magic that he was able to get away with shortcomings that would have ruined any other tenor. The problem for us, those who studied with him, was that we began to develop his vocal shortcomings but did not have his magic to compensate. You felt it. You could come into the room and not see him but sense, there was Schipa over there behind the door. It was amazing. The presence was that palpable. (Zucker)

...resolution

Everybody went to hear his "Una furtiva lagrima". The scene in which he is about to drink the love-potion is one of incredible unpretentiousness. As Nemorino, he was such an innocent, simple farmer that he brought him to life. It was simply something very special. (Sala)

McCormack

scene:

St. Mary’s Pro-Cathedral in Dublin. Oliver O’Brien, son of Vincent O’Brien, the man who discovered and taught John McCormack, tells the youths in the Palestrina Choir, the group in which McCormack debuted in 1902, about their famous predecessor.

music:

Donizetti, Franck, Mozart, Brahms, Irish ballads

analysis: Il mio tesoro (Don Giovanni, Mozart), 1916

Quotes from the film’s exposition...

McCormack has often been criticized worldwide for singing what musicians would consider second-rate ballads and music and yes, he did. But McCormack never descended to second-rate music. If he sang a ballad that was trash he would raise it up to his standards. (Oliver O’Brien) McCormack was not an exciting singer, but he was exquisite. He was a touching singer, but not a deeply moving one. An affectionate singer, a caressing singer, a loving and lovely one. He can make you cry through nostalgia and melancholy. (Zucker)

...from its development...

It was a performance of Don Giovanni that Furtwängler was conducting: when John sang the "Il mio tesoro" Furtwängler put down his baton and led the applause. (Oliver O’Brien) One should be cautious with the word “perfection”, but that really was perfect. I cannot think of any recording to match it. Others sing this piece magnificently, but this performance was hewn from marble. (Kesting) McCormack had the ease of emission that is associated with 19th century tenors and had one of the most masterful breathing techniques. Sometimes you can’t tell when he takes breath. When I began to study singing he was my idol because of his technical perfection. (Zucker) McCormack had a good vocal technique all his life. But he gave up opera young, he wasn’t 39. That was because he was totally independent financially. In one year alone he would make 300.000 Dollars which was huge. He was the Pavarotti of his time. (Smith)

...and from its resolution

He had brought so much joy to all of us. Please God, I hope for the next generation, maybe they wake up that there was such a wonderful man in Ireland who sang all these beautiful songs. (Mary Breene)

Slezak

scene:

A meadow above Lake Tegern, where Slezak spent his vacations. The Bavarian farmers still remember theit former neighbour.

music:

Meyerbeer, Millöcker, Rossini, Verdi, Raimund, Hugo Wolf, Robert Stolz

analysis: Ora per sempre addio (Otello, Verdi), 1912

Exposition...

We remember him as a film comedian, a humorous writer, and generally as a man with great sense of humour – but that was only in the last phase of his life. The heroic singer, the giant of a man, his Manrico, Lohengrin, Radames – they all tend to be forgotten. (Höslinger) He is a heroic tenor without the slightest shadow of baritone. A singer with no influence from Caruso, who darkened the voice and made it sort of masculine. (Kesting)

...confrontation...

Slezak swings up into the greatest heights with no effort at all, in a way that has remained unique to the present day. Not even Pavarotti could sing at this height in such a relaxed way. We can hear that Slezak hardly needs to exert any effort at all to rise to these regions, and for a tenor these are the glaciers or the Himalayas. (Kesting) Many singers will end up emphasizing resolutions of dissonances, notes that occur on weak beats. You don’t find that with Slezak. Once the dissonance is passed he will make a diminuendo, and thereby he reflects in the vocal line what is happening harmonically. He mirrors the harmonic structure. (Zucker) He beguiles you, he wooes you, he caresses you, he makes love to the song. The song sung by just about anybody else would be trivial, would be kitsch. When he does it, it becomes delicious art. (Zucker)

...resolution

These songs bring out the kind of person he really was – a deeply sensitive person. Slezak suffered terribly as a result of the changes in our century. For him almost the whole world disappeared with the collapse of the monarchy. In all the years after 1918 he never found what used to exist. (Höslinger) I sent him this card on his 70th birthday, and he answered at once. (Schlesinger) "Dear Lady, I must thank you most sincerely for your kind thoughts and the lovely painting with all my roles. I was deeply touched. May God grant that we may soon return to life. I kiss your hand most humbly – Slezak."

Melchior

scene:

Lauritz Melchior’s Danish-American son, Ib, in pursuit of childhood memories in Chossewitz, East Germany, where the family lived in the 1930s.

music:

Meyerbeer, Wagner, Verdi, Grieg, Leoncavallo, Schlager songs

analysis: Gott warum hast du gehäuft dies Elend (Otello, Verdi), 1930

Exposition...

Near the end of his life, Wagner wrote in desperation to a singer: "Why on earth did I give all the demanding roles to a tenor?" He never found him. The first and maybe last singer to define Wagner’s heldentenor was Lauritz Melchior. (Kesting) He could entice all the talent out of me that I had. (Varnay) In Parsifal there are long stretches where Parsifal hasn’t got to be on stage. He then used to go off stage and have a drink. But who wouldn’t prefer a recording with him singing Parsifal than to have to listen to the average tenor? (Scott)

...confrontation...

This is the Tristan score my father bought in 1912. He listed every occasion on which he ever sang Tristan. He sang Tristan more than two hundred times. (Ib Melchior) Melchior started some performance tired and ended fresh. He could have sung Siegfried twice in succession, he said. (Kesting) He had a brillant voice, but remained a natural lad. He moved in the way he thought Siegfried would have moved if Siegfried’s name had been Melchior. (Varnay)

...resolution

There has never been a heroic tenor to equal Melchior. Which is amazing if one considers that today everyone has got orange juice and cod liver oil from the earliest days. Everybody has got the physical strength to survive an endless regime of Wagner tenor roles. The reason is quite simply just because opera singers no longer think in terms of thinking out to the back of the hall. It’s the gallery’s people which you have to affect. (Scott)

Tauber

scene:

Debate about Richard Tauber at the “Recorded Vocal Art Society” in London, the city to which Tauber had to flee during the Third Reich.

music:

Bizet, Leoncavallo, Schubert, Mozart, Offenbach, Tauber, Srauß (overture to “Fledermaus” conducted by Tauber), songs

analysis: Es war einmal am Hof von Eisenack ( Les contes d’Hoffmann, Offenbach), 1928

Exposition...

Tauber could attune his voice to the orchestral sound and to the instruments. Only great singers who can sing from the organic essence of the composition have this gift. (Kesting) That particular charme, that particular thing he had… In the films, it’s the women who are swooning. He hit a certain tone, a certain pitch that turned them into rubber. (Castle)

...confrontation...

One of the most remarkable things about Tauber was his musicianship. When he sings an aria like the legend of Kleinzack, you can hear this when he changes from major to minor key. He changes the key on a note before the orchestra does. This requires the most subtle musical sensitivity. (Scott) Nobody has ever conducted a Strauss waltz like Tauber doing "Tales from Vienna Woods". The conductor’s triangles were no equal triangles. There were accents which one never dreamed of. I shall never forget the freedom, the extraordinary musicality of Tauber’s conducting a Strauss waltz. (Aprahamian)

...resolution

The first time I saw him I disliked him intensely. He was singing Goethe in a musical by Lehár which I could not stand. Then I heard him singing Ottavio. That cured me. I have never heard anyone, before or since, who could sing Mozart so purely and beautifully. (Bergner)

Dialogue with Eternity

scene:

Music lessons with Peter Feuchtwanger in London, who applies the principles of bel canto to piano playing.

music:

Meyerbeer (de Lucia, Bonci), Chopin (Carol Cooper), Schipa (Tito Schipa), Verdi (Caruso, De Lucia), Donizetti (Joseph Schmidt, Stefan Zucker), Wagner (Melchior), Bach-Gounod (Moreschi), Strauß (Schwarz/Tauber), Leoncavallo (Lieban)

analysis: Alessandro Moreschi (the last castrato): Ave Maria (Bach-Gounod), 1904

Exposition...

The record is a wonderful invention, it repeats something which cannot be repeated. Miracles can only happen once. (Feuchtwanger) The gramophone created a new relationship with the musical time. When a singer holds a top note I forget time. If I hear the same note many times over on a record the effect is totally different. (Kesting)

...confrontation...

“Bel canto” – it’s so vague that I sometimes think the term should be banned. Its principle use is a kind of negative one. We know what isn’t bel canto and it’s useful in that respect. In a real bel canto singer it’s not simply a matter of a smoothness and flexibility, but an element of phantasy enters as well. The obvious example is the Neapolitan Fernando de Lucia. He takes all sorts of liberties which wouldn’t be allowed by any conductor today. But when you listen to him your first instinct is to say, “how poetic”. “Poetic” is almost as vague as “bel canto” itself, yet you do mean something by it. That the imagination of the singer has taken flight. That these are no longer notes on paper. (Steane) De Lucia still understood the Latin of singing. It was still a living language in those days. (Kesting) Decorations of the sort that De Lucia has used were absolutely common to Italian singing as far back as we can trace it in history. These little quick notes remained an essential part of Italian singing until it was stemed out in our century. (Crutchfield)

...resolution

Gramophone records had an enormous levelling effect on singing. Singers had to learn to produce a model performance. (Kesting) The only ideal moment is the here and now. The unique value of the moment is its irreproducibility. (Splett)

Caruso

scene:

A gathering of older New York Italians in Luigi Rossi’s store, Grand Street, Little Italy. Caruso had become the figure of identification for Italian immigrants in New York at the beginning of the century.

music:

Meyerbeer, Verdi, Donizetti, Cardillo, Halévy, Leoncavallo

analysis: Una furtiva lagrima (L’Elisir d’amore, Donizetti), 1904

Quotes from the film’s exposition ...

Caruso was trained in the old school of bel canto, singing on the breath. He used that technique even up to his last recordings but fused it with the expressive gestures of verismo. Aesthetically, it was bold – but brillantly bold. (Kesting) Caruso was critisized in Naples for being in essence a vulgar singer because he did not do the diminuendos of, say, Fernando de Lucia. Caruso provides many thrills. But on balance his effect on singing was to make it less expressive, less interesting certainly from a musical point of view because Caruso tended to sing at full volume most of the time. (Zucker)

... from its confrontation ...

Fred Gaisberg travelled to the Continent to record great singers. In Milan, “Caruso poured the liquid gold of his voice onto the wax cylinders which we couldn’t change as fast as he sang”. He sang ten arias in half an hour and picked up hundred pounds. Three months later the company had made 15,000 pounds. (Kesting) Once he came to the Met this was his opera company. If you think in terms of todays singers – they don’t devote themselves to one company. They fly everywhere. Caruso came to New York in October, usually, he stayed until the end of April and he averaged more than fifty performances a season. (Tuggle)

... and from its resolution

The great success of Caruso led the tenor voice to become a media phenomenon, as René Leibowitz once wrote. So Caruso, who had had such extraordinary success on stage and had outshone all his contemporaries, was the singer to imitate. In the Twenties, Caruso’s Canio aria was imitated for the Caruso sob, not for his phrasing. (Kesting) Caruso is the archetype tenor. (Scott) When you were in the audience you became part of Caruso. You felt that you were inside his body. It was a subnormal voice. It would open up after you thought it was finished. That was Caruso’s voice. (Sisca)

Texts

Bel Canto – An Idea Comes of Age

Documents and Artefacts

Peter Feuchtwanger: Bel Canto on a Percussion Instrument?

Jürgen Kesting: Enrico Caruso and the Voice of the Tenor

Listening with the Eyes – Interview on “Belcanto”

Christoph Schlüren: Cantability

Bel Canto – An Idea Comes of Age

by Jan Schmidt-Garre

When we were looking for a common denominator, a name, for our project, one word soon forced its way to the forefront: Bel canto. This term seemed to be the best one to unite all the tenors of the first half of this century, whom we planned to present in twelve portraits and to bring back to life with a huge quantity of historical documents. They all served this ideal of beautiful singing in which the main stress was always on perfect intonation, beautiful sound, and the perfect balance of the voice. In this sense, Bel canto ought to be our ideal as well to the extent that we are concerned here with an artform, singing, and not primarily with biographical material, anecdotes, or attempts to conjure up a vanished age. For this reason, each portrait centres on the critical analysis of one particularly informative recording, explained in advance by Jürgen Kesting. The second component that we developed for each film was a scene charged with the appropriate atmosphere to present the environment and the world in which the singer lived, in the most tangible possible form, as this was the historical background of his singing.

The many discussions we held during the course of this work with music historians specialising in singers, experts on the voice, and present-day singers gradually changed the superficial, almost slangy concept of beautiful singing that had guided us up to then. The historical phenomenon of Bel canto pressed its way into the foreground and pushed the synonym for successful singing aside. We realised that music historians had defined Bel canto as nothing more than the stylistic requirements and the necessary vocal skills of the Italian repertoire in the early 19th century, as composed by Rossini, Bellini, and Donizetti, and had indeed only seen these works as a derivative of the original Bel canto composed in the 18th century by Handel and Scarlatti. The break-through of the rugged, positivistic 19th century into this world, dominated as it was by the canto fiorito – artificially decorated singing – of the castrati singers, was marked by the virile high C with chest resonance. It was heard for the first time in 1831 in the opera house of Lucca.

Under the impact of this historical redefinition of Bel canto, our interest turned first to the tenor who represents a stylistic bridge to the early 19th century: Fernando De Lucia. In a thirteenth programme we devoted as much time to him as ever an optical medium allows, considering that no moving pictures of him exist. As John Steane said in discussion with us, "In a real Bel canto singer it’s not simply a matter of smoothness and flexibility but an element of phantasy enters as well. When you listen to Fernando De Lucia your first instinct is to say, ‘how poetic.’ ‘Poetic’ is almost as vague as ‘Bel canto’ itself, yet you do mean something by it: that the imagination of the singer has taken flight, that these are no longer notes on paper." With De Lucia’s singing still echoing in our ears, we then listened to Gigli’s serenade from Iris or Björling’s Ingemisco from Verdi’s Requiem as testimony to a new age, one that had nothing to do with the historical Bel canto in which De Lucia had grown up. And indeed, our tenors of the 78 era no longer learnt the "Latin of singing," as Jürgen Kesting called it; they sing contemporary music, verismo music, and then only gradually start turning to older works such as a little Mozart, Verdi, a Gluck aria or two, and perhaps a few comic roles by Rossini. Historical Bel canto plays no essential part in the repertoire of our protagonists.

And so, as we listen to the great recordings by Tauber, McCormack, Gigli, or Björling, we know that they are something new – but can still pick up a trace in them, an echo, of the old school. Suddenly we rediscover our original intuition of that which Bel canto could have been. In Tauber’s unique ability to anticipate with his voice the modulation the orchestra was about to make, in McCormack’s perfect intonation, or the unearthly beauty of sound in the voice of Beniamino Gigli, we can see the traces of the great Bel canto ideal about which singing teachers of the 18th and 19th century wrote. Although the historical Bel canto has vanished, the aesthetic principle of Bel canto is coming back to life; it has survived, and is making its mark in the really great, revitalising recordings. Bel canto appears here to have been turned into something nobody had expected, into a universal principle of art: the imperative of discretion, the economy of resources, the unsentimental objectivity, the free, spontaneous ability to let things evolve.

Documents and Artefacts

Presented at the IMZ and EBU workshop "On Making Documentaries about Music and Musicians"

by Jan Schmidt-Garre

We have been talking a great deal about music today and about the right way of staging music or musicians in a documentary. The word indicates that we are concerned here with documents, and I would like to develop a few thoughts on this subject: on the relationship between reality, depiction, and fiction, between the document and the artefact.

1. Document

The presence of the camera changes the object. Light, framing, camera movements, and later the selection and context rob the document of its innocence and convert it into an artefact that is determined by the medium and the author at least as much as by actual reality. "The medium is the message", as Marshall MacLuhan said. Is the pure, innocent document a fiction?

Example 1: Callas/Habanera

Sometimes, however, the message is the message. This single shot contains everything: musical theatre, the art of singing, identification, distance, irony, devotion. The power of this document protects it from being devoured by the voracious medium. Direct cinema. Cinéma vérité. This ideal may be naïve in terms of epistemology, but it is attainable in rare and fortunate cases, and it was with it that I approached my first major subject as a film-maker, the conductor Sergiu Celibidache. I accompanied him for three years to rehearsals, on concert tours, and to watch him teaching. How could the pictures we took of Celibidache achieve the directness and authenticity of the pure document? "It was an animal film", the cameraman said when filming was finished, and indeed we had lain in wait for a tiger in the jungle. Celibidache did not seem to notice we were there, and his vital self-confidence prevented him from changing by one iota from his normal self when the cameras were running. And the musicians who were playing under his baton were so much enthralled and challenged by his authority, that questions of shame or vanity simply never arose.

Example 2: Celibidache/Forza del destino

However, it is possible for a crack to appear in the self-contained system of Cinéma vérité if reality fails to stick to the agreement, which is: we observe you and you don't notice us. If the document suddenly looks at me, it catches me red-handed as a voyeur. It turns my own weapons against me and forces me into an uncomfortable intimacy, an intimacy that I had not asked for. Suddenly a window opens onto the actual reality behind that which is being depicted.

Example 3: Celibidache/Forza del destino/Glance into the camera

2. Artefact

My film "Bruckner’s Decision" also started as a documentary. A brief episode in Bruckner’s life had caught my interest, a time of crisis and transition. He had been sent to a water spa in 1867 on account of psychological problems. He spends the summer there and finally, at the age of 43, takes the existential decision to become a composer. Everything that follows flows from the decisiveness he has at last gained: his move to Vienna, his position as a professor of composition, and most particularly his powerful Masses and symphonies. I could not draw on any documentary film material from 1867 so I decided to use what is now called "dramatic reconstruction", and created my own artefacts. In the sound I combine these artefacts with authentic documents from Bruckner – letters –, and I complement and reflect them with letters from a fictitious person whom he meets at the spa – another artefact.

Example 4: Bruckner’s Decision/Bad Kreuzen

The film met with approval and objections, but there was one accusation that was never made, and for me this is the greatest compliment of all: my film was never accused of falling to pieces, of trying to combine too many disparate elements. In addition to the artefacts from Bruckner’s spa treatment there is also documentary material in it of a present-day Bavarian Corpus Christi procession, modern church-goers leaving after the service, Bruckner as a child in St. Florian, clouds, photographs from Mexico in the 1930s, and a painting by Manet. Bringing these heterogeneous elements together into one consistent whole was in my view the challenge of the editing-room, and it was here, as with all my films, that the creative work actually took place. The experience I have had of artists like Bruckner and Celibidache, and his teacher Furtwängler (about whom I am currently making a film essay), is constantly challenging me to look for a self-contained form in art, an art that does not naively avoid, let alone deny, the ugly, the disturbing, the destructive, but attempts to integrate it into a coherent whole. I defend this principle against the over-powerful tendency of our day to present a torso, a fragment, an open form. Every cut that I make in the editing-room is an attempt to re-create the innocence – reconstruction in the age of deconstruction. In the editing-room we played around with our artefacts and tried out different combinations, and suddenly, again, a window opened. Two shots that we had filmed independently of one another revealed themselves as a straight shot and its reverse angle. We see what Bruckner is seeing. We see with his eyes, we are suddenly inside his head. This creates identification and empathy. And that is how "Bruckner's Decision" turned into a feature film.

Example 5: Bruckner’s decision/glances

3. Artefacts from documents

"Belcanto" is a series about historic tenors, and came about not only because of my enthusiasm for these magnificent musicians but also because there are exciting documents available on the great singers from the early days of sound films that hardly anyone knows anymore these days. These documents are not immediately accessible; there is a layer of cultural dust on them that we first had to remove. This starts with the technical parameters; finding the original negatives from which we can make a tele-cine transfer and define the best possible framing, avoiding the cut-off heads, and finding the right running speeds – which can be anywhere between 18 and 24 frames per second – as this can after all affect not just the pitch but also the colour of the voice. However, more than this was at stake: we had to bring historical material to life. The old film documents had to be integrated as perfectly smoothly as if we had staged them today specially for our portraits. The material we were filming now, on the other hand – the atmospheric scenes and interviews with experts and eye witnesses, and so on – had to be brought close to the historical documents. So we filmed in black-and-white. We tried to bring all the components together into a flow of film. Historic locations such as the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires or the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth were not filmed as dead pieces of architecture but as the backdrop to real live scenes. Photographs are not cut in as lifeless stills, but they appear in the hands of the people we are talking to, again, as parts of a scene being shot today. Symptoms of the past that you can analyse and categorise with polite interest turn into symbols that lead to an understanding and experience here and now, to real empathy. Staged situations for bringing historical material to life: artefacts from documents.

Example 6: Caruso/Little Italy

In "Belcanto" we worked to a strict pattern. We were involved in a 13-part series, so we had to take care of recognisability, of a clear graphic profile, and so on. At the same time, however, we tried not to lose sight of the need for just a little irritation, for those windows in the television screen or on the cinema screen through which actual reality flashes at occasional moments. We tried once again to create structures that were so stable that they could even still carry the moments of disparity without assimilating them in a "kitschy" way. There was such a moment in Ireland, in a meeting with the John McCormack Society. Elderly McCormack fans meet every Thursday for no other purpose than to listen to records together.

Example 7: McCormack/Society

The devoted glance of this lady, in my view, brings John McCormack, who died 57 years ago, back to life: his patriotism as an Irishman and his faith; but at the same time it shows what he still means to Irish people today – and how long ago it all is. But in return for that this shot has to be maintained for such an embarrassingly long time.

4. Documents from artefacts

Celibidache's glance into the camera had opened a window into the reality behind the documents of Cinéma vérité. This is, because a totally different picture is seen from the Divine point of view from the one we were filming: musicians with instruments and the conductor in front of them, yes, but also: spotlights, cables stuck together with tape, microphones, rails, cameras, technicians with headphones. Revealing this situation as it actually exists is the principle behind my film "Opera Fanatic".

Example 8: Monty Python/a film within a film

The idea behind "Opera Fanatic" came from outside: Stefan Zucker, a brillant New York opera expert and singer claiming to be listed in the Guinness Book of Records as the world’s highest tenor, was planning to go to Italy and interview the great female singers of the 1950s and 1960s. He asked me if I would like to join in. In order to get a clear picture of a project I like to place myself in the role of a doctor and break the development process down into the three phases of anamnesis, diagnosis, and therapy. The anamnesis starts with the initial idea: a subject, material, or as in this case a suggestion from outside. I start researching and building up a personal relationship with the material. Here, that consisted of listening to records of the singers, studying their biographies, their repertoires, and so on. This leads to the diagnosis. I try to recognise the material as such, to take hold of it. What kind of a project is this? Actually, in this case the interviews with the old ladies were actually only secondary; the real subject of the film was Stefan’s journey through Italy, his search for the great pathos of a long-vanished opera, his search for childhood memories, and perhaps even the search for his own mother, herself an opera singer of those days, who used to take him with her when she made guest appearances in Italy. Once the material has been diagnosed the therapy can start: how can this be realised in an adequate way? I decided to locate the film on two levels: Stefan’s travels through Italy in an old van, with all his expectations and comments, filmed with a hand-held camera on Super 16 mm, and in parallel with that the interviews with conventional lighting, the camera on a stand, shot on video. A film within a film, documents from artefacts.

Example 9: Opera Fanatic/Gencer

The only "true" side of the interview situation in Cinéma vérité terms is the interview situation itself, with all the cables, artificiality, and nervousness. How will Giulietta Simionato, whose apartment we have turned upside-down, react to Stefan Zucker, who is all a bit of a mystery to her and now asks her, in his castrato voice and affected Italian: "Let us assume we are in the 1930s and you are at the beginning of your career. What would you do different?" We see her sitting all amongst the cables and lamps, we see Stefan Zucker, the sound engineer, the video-cameraman, and we see the video-camera waiting for the answer. She needs a few seconds, and then: "I wouldn't do it again."

Example 10: Opera Fanatic/Simionato

This sentence, in this situation and after this pause for thought, comes fairly close to the ideal of the directness and authenticity of Cinéma vérité. But even here, again, it is not Giulietta Simionato as such who is speaking. There is no key-hole through which we can see her. But there is the actual Giulietta Simionato, here and now, in this situation, with this face that she is showing to us. And in order to understand this face I open the context out as wide as it will go and thus try to reach the limits of the observation situation. I unmask the documentary situation of the interview by documentary means as artificial: documents from artefacts. However, even in "Opera Fanatic", which so to speak institutionalises the open window and turns it into a principle, there is a moment when reality breaks in and bursts out of the framework of the film.

Example 11: Opera Fanatic/Pobbe

Is Marcella Pobbe being compromised here? Is Stefan Zucker being compromised? The question is connected to my subject because a document that is created without the knowledge of its protagonists has, in the nature of things, a greater potential for authenticity – if only of a somewhat negative kind. Every viewer will answer for himself the question as to whether "Opera Fanatic" exposes its heroes. I can only try to explain my attitude to those scurrilous, weird phenomena that keep turning up in my films. My attitude is determined by empathy and identification, and at the same time a sense of distance. This may sound like a paradox, and perhaps even perverse, but as I hope the films show it is possible. I like Stefan Zucker but at the same time I recognise very clearly what an impudence this man is. I identify myself with his obsessions, but that does not mean that they become mine. I never laugh at anyone but I welcome and provoke laughter. I think this attitude is camp. Camp is not ironic and not cynical; it is a broken and desperate yearning for authenticity that sometimes can only be achieved in this kind of strange indirect way.

5. The document recovered

Example 12: Monty Python/a film within a film within a film

Just as the tortoise kept ahead of the hare, reality always seems to be a step ahead of us. Not even exposing the observation situation releases us from this dilemma. There is always an irreducible rest left over, a "strange loop". A thousand veils, and no reality behind them as Lyotard says? There is one escape route, and this is art: somehow the absolute artefact. To put it in the words of the Romantics, "All one can actually do is write poetry – everything else is inexact." And the absolute document?

Let’s go back into the editing-room, whith the cans that came out of three years’ filming Celibidache. Here the trilogy of anamnesis – diagnosis – therapy is repeated. The first step is to gain the full acquaintance of the material, to assume ownership over it, to master it – this is the most laborious and unproductive part of film-making. I keep trying to shorten it, or delegate it to someone else, but it doesn’t work; the author himself, like a good doctor, has to go through this whole process. In the diagnosis the material is then recognised and evaluated: where in this unstructured continuum does a take start and end? What kind of a character does it have? Does it belong to the exposition? Or to the resolution? What is the inner dynamic of my material? The only virtues that help here are honesty – the material must be recognised and accepted for that which it is – and humility: I must not demand too much of the material, or force anything onto it of which it is not capable. I can and must work with that which is given, and not with unrealised intensions or prefabricated theories, I must not overrule or misuse my material. "Going on from the given" is Celibidache's definition of the legato, and for Furtwängler the highest aim for any musician is real legato playing. Interpretation, regardless of whether it is of musical or film documentary material, would then mean: recognising and realising the forces resident in the material. Just as good therapy can only be the kind that helps the body to heal itself. Each detail thus finds its position out of itself, and the film in its entirety takes on the force and necessity of an organically grown structure. Our document, having lost its virginity during the course of this long story of voyeurism, manipulation, and corruption, can regain a second innocence. The film then no longer needs any window onto actual reality because it has become a window itself, the icon through which reality reveals itself. Just as in Zen: "When we reach the ground and the origin, the mountain is once again a mountain and the river once again a river, the meadow is green and the flower is red."

Peter Feuchtwanger: Bel Canto on a Percussion Instrument?

Pianists and piano teachers all too often hear experts say that the piano is a percussion instrument, and that it does not matter whether the key is depressed by a pencil or by a finger, whether it is a construction worker or a pianist who strikes the note, since the quality of the tone depends merely and entirely on the speed of the action. However, most of us suffer when the piano is being tuned and the tuner hammers out every note con furore. Pianists try to produce a beautiful tone without consciously thinking how quickly or how slowly the key must be depressed. The great difference between a construction worker and a sensitive pianist is, after all, contained in the capacity of imagining the sound beforehand – if this is not considered as the first priority, music making should be given up altogether.

Why is it that the pianists of the past were much more concerned with beauty of tone than so many pianists of the present day? Perhaps because we live in a noisy world, we often play in larger concert halls, which makes us believe that we have to force the tone. We also allow ourselves to indulge in ugly body movements at the piano, movements that interfere with the tone production and which would have been unthinkable a few generations ago. Above all, I think, we ought to search for the reason in the fact that the art of singing, the art of bel canto has been lost. The singing of today has little to do with the past achievements in this field – and the pianist has lost the ideal example of bel canto from its Golden Age.

The human voice is without doubt the most beautiful of all instruments, and as an instrument the voice has not changed throughout the centuries. What did change however, is the tone production and the training of the voice. In comparison to the singers of the Golden Age, the singer of today does not have the correct vocal training to create the dificult rôles of the bel canto. In difficult passages we often do not hear the notes, but an approximation of these notes, most of the time drowned by the orchestra anyway. But even in simple passages the voice is wrongly placed, the intonation is faulty and the so-called sliding up to a high note (not to be confused with a genuine portamento) has become an everyday mannerism.

Today we are very lucky, to be have the opportunity to listen to the last exponents of the genuine Italian bel canto, since a vast number of original recordings have been transfered onto CD’s. Alas, only a few of today's pianists take advantage of this privilege, although pianists are the ones for whom it would be of the outmost importance to hear these recordings, time and time again. Only in this way it is possible to develop true understanding for the piano music of the 18th and 19th century. Vladimir Horowitz never stopped talking about bel canto singers, especially Bonci and Battistini, and Arthur Rubinstein recalled how he was moved to tears by the singing of Kathleen Ferrier.

We, pianists have the disadvantage – some people may call it an advantage – that our tone is ready-made, waiting for us in the form of a key on the keyboard, whereas singers or string players have to create their own tone. But, if the pianist does not hear his tone before he plays it, for instance: if he does not hear the leading note B urging towards C differently from the B which comes from C and descends to A, if he cannot hear this difference and if he plays both B’s in the same manner, then an essential aspect of music-making is lost.

Johann Sebastian Bach wrote in the introduction to his Inventions about the singing (cantabile) manner of playing: "Above all" the Inventions should teach "a cantabile manner in the playing." His keyboard music is very much influenced by the voice and emphasizes the vocal element. It is all the more incomprehensible that most pianists play Bach's music so aggressively, and mechanically. (Bach himself played so calmly that one could barely see his fingers move.)

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach advised pianists to listen to good singers, and to sing their instrumental parts in order to develop the right understanding for the correct execution. Mendelssohn said: "To be able to express genuine emotions in piano music, one must listen to good singers. One learns from them much more than from any instrumentalists." In his letters from London we find valuable mention of singers like Maria Malibran, Henriette Sonntag or Giuditta Pasta. His friendship with Jenny Lind and his admiration for her influenced many of his works. Schumann said: "Never miss an opportunity to hear a good opera," and recommended pianists to sing in choirs. Clementi’s mature style changed radically by having listened attentively to great singers. Many opera paraphrases and lied transcriptions bear testimony to the fascination that singing held for Liszt, Czerny, Thalberg and their contemporaries.

We know from the writings of Chopins’s pupil Wilhelm von Lenz, that Chopin spent a considerable time in order to make him grasp how to descend from G in bar 2 to C in bar 3 – in the C minor Nocturne op. 48 No. 1. The G was either too long or too short. Chopin was never satisfied. While teaching, he would often refer to Giuditta Pasta and to how she would sing a certain phrase. Let us reflect when playing these two notes, whether the singer would make a portamento between them. It can help us to imagine a word and contemplate whether it would be appropriate for the two notes to be sung on two syllables or just one, whether the word would start with a vowel or with a consonant, or whether perhaps the C would start with a new word… All of these problems are much easier solved by studying the arias of Bellini, who so greatly influenced Chopin. Even on his deathbed, he wished to hear once again his favourite aria "Ah, non credea mirarti" from La Sonnambula.

It is incredible and awe inspiring, how vast the number of singers, male and female was at the beginning of the 20th century. Thousands of records bear witness to their phenomenal skill although the decline of bel canto had already set in and the verismo style caused many singers to force the voice with exaggerated expression. Manuel Garcia, brother of Maria Malibran, one of the most important teachers of bel canto, said that one should never use one's resources to the utmost, as this would always lead to self-ruin and, in the case of singers, to the ruin of the voice. Pianists can learn from this statement, that moderation is not only a virtue but a necessity. Only discipline and reflection can lead us back to the great ideal of bel canto.

Jürgen Kesting: Enrico Caruso and the Voice of the Tenor

Nothing is more attractive to the imitator than the inimitable. The fact that, as Luciano Pavarotti has said, “all tenors of the Italian genre have taken Caruso as their model”, leads at once to the conclusion that a stylistic trend came to an end with him, or even became frozen rigid. The question as to the reasons for this orientation towards one single super-ego, however, is never asked; indeed, it is unfortunately even suppressed. This makes the statement by the composer Sydney Homer, whose wife Louise often sung opposite Enrico Caruso (1873 to 1921) at the Met, all the more interesting: “Before Caruso came along, I had never heard a tenor who sounded remotely like him. After his time I have heard one voice after another, large ones and small ones, high ones and deep ones, which tried to be similar to his, often with great effort.”

One reason for this was the “media-fication of the tenor voice”. With the ten gramophone records which the 29-year-old Neapolitan tenor recorded as the Grand Hotel in Milan on 11th April 1902, he made the record into a medium. The reverse is also true: the record made him. He created the basis for that which one could call “canned fame”, which all his colleagues then also wanted to enjoy, even the older ones. Barely a year later, a dozen tenors of the Italian genre had followed him into the recording studio – not to mention the castrato, Alessandro Moreschi (1858 to 1921), whose first recording was made a week before Caruso’s. They are the distant, and unfortunately dull, echo of a tradition that had already died out even then.

When Homer, who had been born in 1870, started training at the Scuola di San Salvatore, the art of the castrato already lay half a century in the past. Rossini (in Aureliano in Palmira, 1816) and Meyerbeer (Il Crociato in Egitto, 1824) were the last to have written castrato roles. He became a member of the choir of the Sistine Chapel in 1883 – this is the Pope’s personal choir, and he at once became famous as l’angelo di Roma. His recordings of liturgical – if not always deeply pious – music meet few of the high expectations that Handel, Mozart, Charles Burney, Quantz, Schopenhauer, or Stendhal had sung of the sensational castratovirtuosi of the 18th century. But the sound, however trembling it may be, is an echo of the penetrating, elegiac musical tone of the evirati.

The most interesting tenor at the end of the 19th century was Fernando de Lucia (1860 to 1925), born like Caruso in Naples and celebrated as la gloria d’Italia. He studied at the Conservatorio San Pietro a Majella under Beniamo Carelli and Vincenzo Lombardi, made his debut in 1885 at the Teatro San Carlo as Faust, and within only two years was one of the great starts. Although trained in the belcanto tradition of decorative singing (canto fiorito), he became famous for his singing of “verismo” parts. He sang in the first performances of Mascagnia’s L’amico Fritz (1891), Silvana (1895), and Iris (1898), and in 1893 he sang in both the London and the New York first performances of Pagliacci. He made his first recordings six months later than Caruso, in November 1902, and his last ones in 1920 – the total came to nearly 500, twice as many as Caruso. Because his high notes were “short”, Lucia always had to transpose. The remarkable feature of his relatively dark voice was the pronounced vibrato – originally an artistic device with which the 19th century tenors sang the full note (from B flat’ to C’) with the “head-voice” of voce mista and thus tried to conceal the transition. The Duke’s ballata we can hear the stylistically correct art of decoration, even though it is looked down upon today; it was permissible for long-held notes, modulations, and at the end of a verse, and was indispensable in creating second verses.

Enrico Caruso (1873 to 1921) was a pupil of Gugliemo Vergine and of Vincenzo Lombardi, who as a conductor recognised the need for the voices of his pupils to adapt to the new verismo style (the term “style” is only logical if one regards it as a fusion of music and technique). To simplify, verismo requires a voice with one register, stretching from c to c". Caruso took nearly four years after his debut (on 15th March 1895, in Morelli’s L’amico Francesco) until he could sing a satisfactory B flat’ for the first time; this was as Radames in a guest performance in St Petersburg in 1899. He had already achieved his first great success, in the first performance of Fedora (Umberto Giordano), and came to fame with his debut in the La Scala in December 1900. He gave guest performances in London in 1902, and on 23rd November 1903 he sang the first of 627 performances at the Met, which from then on was to be the centre of his artistic work. In his interpretation of Nemorino’s Una furtiva lagrima, written in 1904 (the third of four recordings), one can still hear all the finesse of belcanto – the soft attack of the note, the cut-glass decorations, the powerful increases in the voice (messa di voce), and the subtle morendi – but at the same time one can already here the emphatic, affective gestures of verismo. He is inimitable in Mi batte il cor, O Paradiso, the wildly lyrical singing of the beginning of the crescendo at Tu m’appartieni. Core ‘ngrato, a canzone about the pain of love, confirms Richard Strauss’ saying that Caruso “sings the soul of the melody”. Leo Slezak (1873 to 1946) studied under Adolf Robinson in Berlin, made his debut in Brno in 1896, and sang from 1898 in the Hofoper in Berlin, from 1900 to 1909 as a guest singer in London, from 1901 onwards under Gustav Mahler in the Vienna Hofoper, and from 1909 onwards at the Met, making his debut there as Othello. As an actor, he has been compared to the actor Salvini. This Bohemian singer, who from 1907 onwards worked further on his technique in Paris under Jean de Reszke, sang a slender, lyrical, heroic tenor with a bright, silvery, and at the same time penetrating voice – nothing like it has been heard for decades. Unlike all the other tenors who followed Caruso, he was able to hear the highest notes, like in Arnold’s aria in Rossini’s William Tell, with a highly concentrated, radiant head-voice.

“Since when have you been a baritone?” asked Caruso, when John McCormack (1884 to 1945) congratulated him as “the greatest tenor in the world”. After winning a singing competition in Dublin, this Irish singer studied under Vincenzo Sabbatini in Milan, and sang for the first time at the Covent Garden Opera in London in 1907. In 1909 he made his debut at the Manhattan Opera, at that time a competitor to the Met, where he applied to be considered in 1911. Somewhat awkward as an actor, he concentrated more and more on concerts from 1912 onwards, and became fabulously rich with recordings of folk–music ballads and folk-songs which sold by the million. His recording of Don Ottavio’s Il mio tesoro from Don Giovanni is a classic interpretation – instrumentally pure singing in perfect form. The long-held, crescendo F’s are pure and silvery, and follow perfectly one after the other like a pearl necklace, and coloratura sung with an endless stock of breath linking the two verses.

Beniamino Gigli (1890 to 1957) regarded it as too much of a burden to be asked to assume the mantle of Caruso. Born in Recanati, he studied under the legendary belcanto baritone Antonio Cotogni and under Enrico Rosati before winning the competition in Parma in 1914. “We have found him – the tenor”, reported one of the adjudicators, Alessandro Bonci (once a rival to Caruso in New York) about the young singer with the golden voice (what a wonderful mezza-voce sound in the Serenade from Iris). After rapid successes in Rovigo, Genoa, and Bologna, he came to La Scala in 1918 and made his debut as Faust in Boito’s Mefistofele, as he did again at the Met in 1920. He sang there until 1931, when unavoidable reductions in fees caused by the world economic crisis caused him to return to Italy and throw himself into the arms of fascism – and a series of kitsch hits from which he never really recovered. In the first decade of his career, Gigli possessed a lyrical tenor voice of an enchanting musical dolcezza. However, as early as the 1920s he reverted, under Caruso’s influence, to the affective gestures of verismo and added sobs and sighs to his performance – a rhetorical expression which, however, if one thinks of the political speeches of the time, was in keeping with the spirit of the age.

“Although he only had a small voice,” said Gigli about Tito Schipa (1889 to 1965), a singer born in the southern Italian town of Lecce, “we all had to bow our heads before his art”. After studying under Alceste Gerunda and Emilio Piccolo, Schipa made his debut in 1911 in Vercelli, as Alfredo in La Traviata. He came to La Scala in 1915, and sang at the Lyric Opera of Chicago from 1919 to 1932, and also at the Met from 1932 to 1935, and again in 1940/41. The fact that he was generally regarded as the ideal of a belcanto tenor is due to a misunderstanding; although his voice was as smooth as satin, with a slightly nasal shadow in the middle range and a full blossoming at the top of his range and his smorzaturi (notes dying away to a breath, as can be heard in Werther’s aria) fulfilling the musical ideal of belcanto, a comparison with De Lucia shows that he was only to a limited extent able to meet the virtuoso requirements of canto fiorito. Even in the musically enchanting recording of Una furtiva lagrima one will not find such elegant decoration as in Caruso’s incomparable interpretation. Nevertheless, he was an artist with a wonderful power of expression.

No tenor has dominated his roles in such a masterly way, nor placed himself so far ahead of his rivals, as Lauritz Melchior (1890 to 1973) in the Wagner field. Even on the most stringent criteria he was the only Wagnerian tenor there has ever been who was absolutely incomparable as Tannhäuser, as Siegmund, as Siegfried, and as Tristan. A pupil of Paul Bang, he started as a baritone in his native city of Copenhagen before retraining as a tenor under Vilhelm Herod, Victor Beigel, Ernst Grenzebach, and the great Wagner expert Anna Bahr-Mildenburg. After he had sung Siegmund in London in 1924, he became the leading tenor at the Bayreuth Festival from 1924 to 1931, still under the aegis of Cosima Wagner. From 1926 onwards he sang in about 500 Wagner performances at the Met.

Booted out by Rudolf Bing, he built up a second and equally great career in films and show business. This Danish singer had a dark, technically perfect “covered” voice which radiated energy in the upper register. It could pour out clouds of music, as in Siegmund’s Ein Schwert verhieß mir der Vater, and endlessly sustained as the live (!) recording from the Met. He was a subtle performer, as is shown in the extremely fine, painful colours of Othello’s monologue from the Third Act of Verdi’s opera.

If one were to make an imaginary ranking order of the best lyrical tenors of the century, Richard Tauber (1891 to 1948) would have to take a leading place, or perhaps even the top position. As his Freiburg teacher Carl Beines said, in his younger years he only had a “thin thread” of a voice. However, after his debut in Chemnitz (in 1913) he graduated in the same year to the State Opera in Dresden, then in Berlin (1919), and then Vienna (1925). Developing in the age of radio and the microphone, Tauber was one of the first media stars, partly on account of his close links with Franz Lehar, whose later works such as Paganini, Friederike, Land of Smiles, and Giuditta were exactly tailor-made for Tauber. Even if Tauber was not above indulging in sweet-and-sickly, sometimes sentimental effects, he was until the end of his days a stylist of the highest rank, supreme in technique, a singer whose singing spontaneously augmented the composition. It is typical of his technique that he attempted to attain the full, rich tone of Caruso, even though this cost him the notes of his upper range; he either had to switch to falsetto or create them nasally. The most attractive aspect of his singing, however, was its supple elegance and eloquence in the ballad of Kleinzack and simple, natural grace of his Lieder – whether he was singing Schubert or a folk-song. One should also not forge that he was an accomplished pianist and an excellent conductor.

Tauber had no B flat or C, but Helge Rosvænge (1897 to 1972) could flaunt them with bravado. Originally trained as a chemist, he studied in Copenhagen and Berlin, made his debut in Neustrelitz in 1921, and then threaded his way – a helpful route for the development of a singer – through the provinces before arriving at the Berlin State Opera in 1929, singing there and in Vienna and Salzburg (1932 to 1939) until 1945. This Danish singer may not have been a detailed stylist, but he was a specialist in versatility: he sang lyrical Mozart roles, minor and heroic Beethoven roles, as well as Wagner and Verdi. Like the Italian tenors of his day, Gigli, Pertile, and Merli, he sang with a powerful, often flaming emphasis – an echo of the political speeches of those years. This gives his recording of Florestan’s aria an incomparably pathetic intensity.

A French singer born in the same year as Rosvænge, George Thill (1897 to 1984), was the last really outstanding French tenor. He was born in Paris, was dissatisfied with his training at the Conservatoire, and went to Naples in order to study under Fernando de Lucia. Whatever he may have learned in terms of pure voice technique from the great Italian singer, in stylistic terms he belongs to a different and much more modern school. After his debut at the Paris Opera in 1924, he sang in Verona, Milan, London, New York, and Buenos Aires, but never achieved any great success of the kind that would have led to a permanent engagement. This was not due to the qualities of his clear, bright, but still strikingly masculine voice, but to his puristic style. A “sigh of disappointment” ran through the Met when he sang in a voix mixte, as one can hear in his recording of the c’ in Salut, demeure – stylistically absolutely correct. In operas by Gluck, Meyerbeer, Gounod, Massenet, Berlioz, and Bizet he is one of the tenors of this century who set new stylistic standards.

Without radio, and the amplifying support of the microphone, Joseph Schmidt (1904 to 1942), who in fact came from Davidende in Romania, would never have been able to have any kind of a career. A physically small man, he made his debut with the Berlin radio by sight-reading (!) Mozart’s Idomeneo, and became quickly famous as a radio and film star with his Ein Lied geht um die Welt. However, being Jewish had to leave Germany in 1933, and he died in dreadful circumstances in a Swiss internment camp in 1942. He was never able to draw on his bank accounts and the money he had managed to rescue. Schmidt had a lyrical tenor voice with plenty of volume, particularly in the higher and highest range (the first Fifth of the lower octave sounds dull and often breathy). The special magic of his singing, however, can be found in the painfully elegiac tones of his timbre. When he sings Eléazar’s aria from Halévy’s “La Juive”, the tone and colour of the deep pain shows that happiness is transient.

Perhaps traditions can best be preserved when they are broken – and if there has been a tenor of the Italian (and French) genre who did not take his line from Caruso, and thus came closer to him than any other, then it was the Swedish singer Jussi Björling (1911 to 1960). A member of a family quartet as a boy, he was already very well trained musically when he started his studies under the great baritone John Forsell.

At his debut as the lamplighter in Manon Lescaut, he sang only a few words, but was soon an up-and-coming star once he had sung Don Ottavio. He made his debut as Radames and Manrico in Vienna in 1938, and in the same year came to the Met, where, with a few interruptions, he continued to sing right up until his early death. Compared with the empathetic singing of his Italian and German colleagues, Björling was a classicist. Interpreting his refusal to indulge in the outwardly emphatic effects of verismoas a lack of spirit would be to reveal a great lack of judgement. Just as Björling was a purist in the forming of the musical line and in tonal shading, he was brilliantly fiery in his phonation. He hit the high and highest notes with incomparable verve. His silvery-pure and elegant voice was not large, in terms of volume, but his projection was so perfect that the high notes ran over his audience like a shell from a gun.

Ex oriente lux, as the saying goes. But which tenor from the eastern hemisphere is well known in the West? Although Russia has always been regarded as the homeland of basses, it is often an acquired taste, one that almost has to be fought for, that can take to the Russian tenor’s often light and nasal (and also guttural) timbre. A special place therefore has to be reserved for Ivan Kozlovsky (1900 to 1993), with his unusual but at the same time enchanting voice. He came from the Ukraine, and was trained in Kiev. His teacher Lysenko, and Lysenko’s wife Muravjova, were still from the Court opera and belcanto tradition, and Koslovski was a member of the Bolshoi ensemble for three decades, starting in 1926, and he even appeared with them at the age of 90 (!) to sing the couplet in the triquet in Tchaikovski’s Eugene Onegin. His lyrical tenor voice admittedly had a silvery-fine timbre, but, like Slezak and Björling, he was able because of his projection to sing roles like the Duke, Faust, and Lohengrin, and virtually all the tenor roles of the Russian genre. How touching and moving it was when he sang the jester in Mussorgki’s Boris Godunov with his age grown tender and meditative with age. Modern taste, which attempts to reduce every kind of virtuoso talent in a singer to an arte povera, would regard the artistic and effective style of this Russian singer as over-mannered; he could spin out phrases like Battistini or Schipa, but that would be to ignore one of the finest echoes of bel canto.

Listening with the Eyes – Interview on “Belcanto”

Author Georg-Albrecht Eckle and director Jan Schmidt-Garre in conversation with Rebecca Fajnschnitt

The Tenors of the 78 Era – the title indicates that the films address the ear more than the eye.

Schmidt-Garre: They adress the eye as well. During our research we were surprised by the amount of film material that exists of the great singers from the first half of the century. Producers’ euphoria about the invention of sound film at the end of the 1920’s led to search for subject matter that would demonstrate its value. Films about music were the ideal topic. And you also shouldn’t forget the star status that these great singers, above all the tenors, enjoyed at the time. The distinction between opera and popular singers only developed over time, stimulated by another revolutionary invention – the microphone. Singers such as Richard Tauber, Beniamino Gigli, Joseph Schmidt represented a combination of Pavarotti and Michael Jackson. McCormack sold 4 1/2 million 78 recordings of "I Hear You Calling Me"! And that was a very delicate, introverted song, sung with the most beautiful intonation and phrasing, without the least bit of compromise for so-called popular fashion. Alone in the 1930’s in Europe there were at least 200 films made about singers which contain wonderful examples of the art of singing.

Despite the large quantity of film material from this time, you also use purely audio recordings, which are often even more interesting.

Eckle: That is what is perhaps new in this experiment; a significant accent was placed on seeing the act of listening. We listen to a recorded document and see someone knowledgeable who provides a ‘running commentary’ about the characteristics of the voice and the interpretation; the viewer can thus listen attentively while receiving analytical insights both optically and acoustically. I think that is crucial for today; we have forgotten how to listen deliberately, knowingly and with focus due to the all-pervasive presence of music wherever you go. Moreover, viewers will experience and remember singers in a completely different manner when based on criteria that go beyond ‘beautiful’ and ‘not beautiful’. We were surprised again and again, especially given the amount of undiscovered film material, by how seeing can make something heard. That is, we listen differently, understand differently, comprehend on the basis of subtle differences transmitted more through the personality than in the purely auditory process.

The films seem to do without many of the common techniques employed in documentaries. There is no commentary, no documentary material such as still photographs, no pictures of important places, etc.