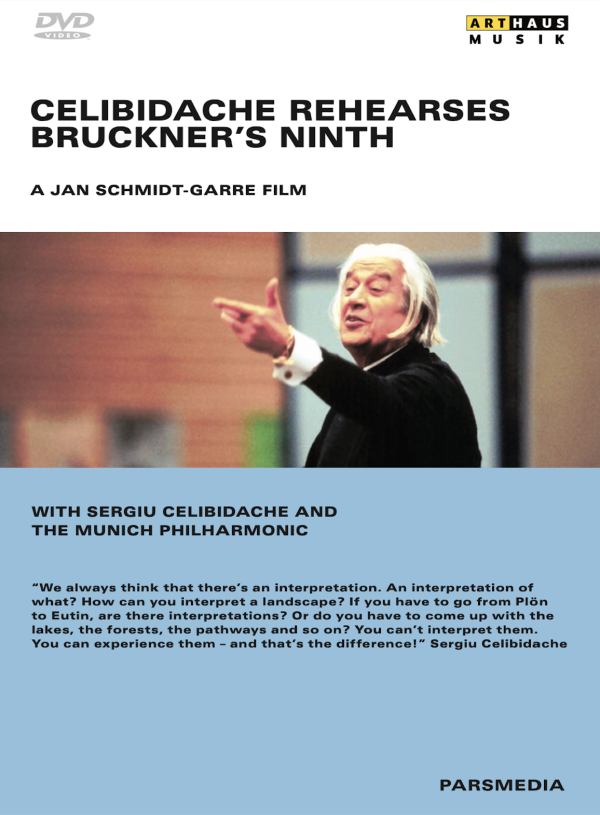

Celibidache Rehearses Bruckner’s Ninth

Facts

Music Documentary, 60 min, 2006Directed by Jan Schmidt-Garre

For a full sixty minutes Celibidache rehearses Bruckner’s Ninth – a key work for the composer, who did not complete any more compositions after he finished the Adagio. It is also a key work for Celibidache, who towards the end of his life frequently returned to working on Bruckner’s late symphonies, performing them in guest appearances all over the world with the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra.

Using previously unreleased 16mm footage, the film focuses on the conductor for unusually long sequences, revealing the musical interaction in this tantalizing process of rediscovering a seemingly familiar piece. In no other documentary film about Celibidache does one experience with such immediacy the moment of music being created. “I breathe with you, and that is the secret of phrasing: where you breathe and how you breathe.”

Cinematography: Karl Walter Lindenlaub

Sound recording: Hartmut Tscharke

Editor: Gaby Kull-Neujahr

In co-production with BR and ARTE

Supported by Media+

Quotes

Sergiu Celibidache

"Take your time. I’m breathing with you. I breathe in there and that’s the secret of the phrasing: where and how to breathe."

"What is a rehearsal? It is, of course, only a labor of memory, of cognition. A rehearsal is not music! A rehearsal is the sum of countless ‘no’s. ‘Not so fast!’, ‘not over the bassoon!’, ‘not so loud!’, ‘not so lifeless!’ ‘not like that’. ‘No! No! No!’. How many ‘no’s are there? Trillions! How many ‘yes’s? Only one!"

"It is really a godless era. So, normally Bruckner doesn’t have much of a chance. People have to come along who are concerned with the question: Is everything that we can see and touch, is that all? He’s incredible. The apotheoses of the final movements can only have been felt, thought out and written by someone who really had a feeling for eternity!"

"We always think that there’s an interpretation. An interpretation of what? How can you interpret a landscape? If you have to go from Plön to Eutin, are there interpretations? Or do you have to come up with the lakes, the forests, the pathways and so on? Here too there are particulars that are anchored in your consciousness. You can’t interpret them. You can experience them – and that’s the difference!"

"You think that’s a theory. The fact is that before we experience the sound, the conceivability of the sound is incredibly important! ‘How should it sound?’ The same goes for conducting. What is my only worry when I start? How is it supposed to sound? It’s the same with you because your fingers alone will never find it. It is an absolutely unconventional leap, that is, it happens in the mind. The conceivability of the sound is what’s most important. It can happen that it’s clear within you but not for your fingers. That’s all possible. But one thing is for sure: if you can’t conceive the sound in your mind, your fingers will never be able to hit it."

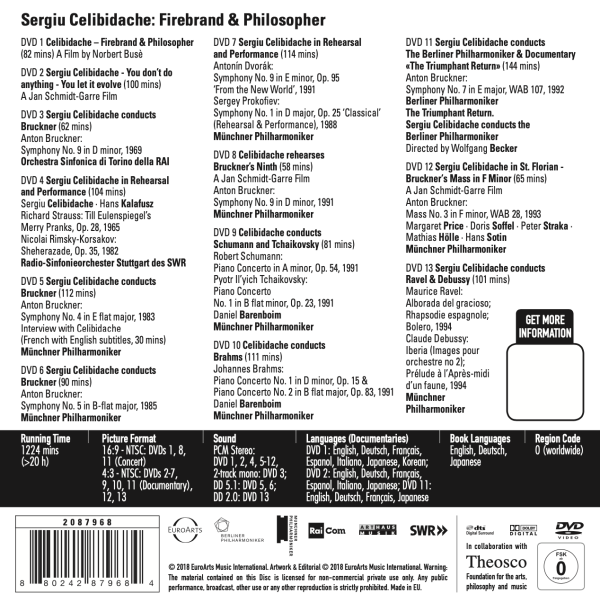

Releases

On Bluray and DVD with Arthaus Musik:

And in a 13 DVD box with EuroArts:

Texts

Sergiu Celibidache: On Musical Phenomenology

Sergiu Celibidache: Quotes

„Celibidache Rehearses Bruckner’s Ninth“ – Director’s Notes

Celibidache’s Presence of Mind

Sergiu Celibidache: On Musical Phenomenology

“Expressive parts must be played more slowly than others."

Frescobaldi

“The harmonies of a presto movement must be kept very simple."

Haydn

“The length of a movement depends on the opposition of its ideas."

Schubert

Music and Sound

Music is not something that can be captured in a definition of thought concepts and linguistic conventions. It does not correspond to a perceivable form of existence. Music is not “something”. Something can become music under certain unique circumstances. This something is sound.

Sound and Tone

What do we know about sound, and ultimately about musical tone? Not much more than the prehistoric human being who, following an inner urge for freedom, found it through inspired search and borrowed it unknowingly from the universe. What is sound? Sound is movement. Sound is vibration. What moves? Material substance moves: a string, a mass of air or metal. We know that everything is movement. If sound is movement, what distinguishes sound – with the potential of becoming music – from other movements? Its own distinct fundamental structures are the same unchanging vibrations. The same number of vibrations over a certain unit of time: such is the nature of musical tone.

Tone and Man

This structure might exist in the world that surrounds human beings; however, it does not appear on the radar of his sensual watchtower. Man, who created the unchanging tone, delivered it from the inert depth of his material environment to the light of his consciousness, or one might say: brought it down from the divine stage. He stretches a length of elastic between two ends and makes it vibrate, blows into a bamboo tube or into a hollowed bone with holes; thereby he unwittingly creates conditions that allow him to transcend his original condition. Initially he is fascinated by the reliability of his discovery. Each time he creates the same conditions he makes the identical experience. His habitual volatile environment does not normally offer such experiences. He has come to know the transience of his environment and all he gets to see of it. The evenly vibrating tone is transient, too, yet for the duration of its existence manifests a permanent, recurring identity.

Overtones

The evenly vibrating tone does not vibrate alone. A host of overtones – not produced by the inventive originator – vibrate along with it and unite in an entirely new resonating multiplicity. Such overtones, which are directly dependent side effects, are immediately subsequent epiphenomena. These side effects displayed by the tone are nothing other than its different unequivocally structured stations on the way to its ultimate disappearance. We see ourselves confronted with the most fundamental phenomenon that gives the tone the opportunity to become music.

The Future of the Tone

The first overtone, the octave, appears later than the main tone, i.e. it is the main tone’s future. However, the octave is not something entirely new. Under melodic conditions it can appear new while being the same thing. The second overtone, the fifth, is entirely new and unmistakably different. It is the actual future of the key tone. In its relation to the main sound and to the other side effects it is overriding and thus inherits all prevalent attributes of the original tone. It is characterized by the Pythagorean relation of 2:3 that constitutes the smallest and the largest opposition of the first prime numbers. It stands in perpendicular position to the main function, which makes it the most stable sound interval. But despite its implied spatio-temporal structure, a tone alone cannot become music. Only the appearance of the next tone makes further dimensions of the expanding activity materialize, which works against the all-enveloping inertia, the all-devouring tendency to disappear.

Onepointedness

We will leave the material aspect aside now and focus on the nature of the human mind. The human mind is a self-contained, indivisible entity, constantly confronted with a multitude of phenomena; it is forever ready to appropriate and identify with what it perceived or to exclude what is impossible to correlate or reconcile. In Sanskrit this unique nature of the human mind is called Ekagrata. The English call it onepointedness: to be oriented towards one thing. It is the non-dualistic nature of our free consciousness. If the mind did not receive and again abandon what it appropriated, i.e. have the ability to transcend, there would be no further possibility for another appropriation. Instantaneous transcendence here and now allows the mind to regain its freedom. This freedom consists of the impartiality that is a sine qua non for the mind’s next appropriation experienced in correlation.

Reduction

The only possible achievement of our mind is its ability to integrate the differences, to eliminate duality of any kind. Consequently it needs to integrate all multiplicity in an evidently self-contained fact. The process of eliminating differences, of integrating all parts to an entity we call reduction. It is not a process of reconstruction, but of one-time and first-time new construction, dependent on one premise only: mutually complementing, internally complementary relationships between the parts or ways of being.

Transcendence

With mature sound perception individual phenomena disappear and the question arises: what remains? What remains is the relationship that can only be experienced through an act of transcendence. The transcending mind neither stays with the first nor the second part of a relationship, but it exceeds both of them and adopts the essence of their relationship. Do relationships disappear? They do. Not, however, like the tones from the physically perceivable sector whence they originate; instead they integrate into a novel, higher unity, which transcends the parts. This unity is the lasting work, the eternally possible function of the human mind.

Climax

Musical articulation always constitutes a process of expansion and compression. The right to persist in the spatio-temporal dimension – the right to continuance – is directly dependent on the opposition. To what point can the expansion extend? How far can the expansion stretch? To the point where it can expand no more. This crucial point of all expansive development is called climax. This turning point where the extroverted direction of the expansion tips over into an introverted one is the most cardinal pivot about which every form of musical architecture is functionally structured. Everything that happens in the expansive phase goes through organic complementing in the compressive phase, which furthers the reduction process. If this is not the case, the end is not the consequential, inevitable result of the beginning. If, however, the end is the result of the beginning, it is simultaneously present with the beginning, as in the act of thinking. Both the act of thinking and the musical act manifest and materialise in the spatio-temporal continuum. But in terms of their essence they stand beyond time, simultaneous.

From a lecture held at the University of Munich on 21 June, 1985

Sergiu Celibidache: Quotes

You can’t do anything other than let it happen. You just let it evolve. You don’t do anything yourself. All you do is make sure that nothing disturbs this wonderful creation in any way. You are extremely active and at the same time extremely passive. You don’t do anything; you just let it evolve.

A rehearsal is not music. A rehearsal is the sum of uncountable ‘nos’. ‘Not too far, not too loud, not above the bassoon, not so dull.’ How many ‘nos’ are there? Billions. And how many ‘yeses’? Just one.

That is the complete training. You have to do at your seats what I am doing at mine. You have to conduct with me. We react spontaneously to what we hear, that is, functionally, as is necessary. Not "this is marked piano, this is marked forte…" – no one is interested in that.

I don’t know if that gives you an idea of what I would like: to emanate from what already exists. The way oil spreads, becoming wider and wider and wider. Not so pointed. Those are notes, but not yet music.

What is the "interpretation" in what we are doing here? It’s nothing else but finding out what the composer had in mind. He starts from an experience and looks for the notes. We start with the notes to come to his experience.

When I criticize him like this he is losing his spontaneity. He will have to find reality by himself. Reality which cannot be ‘interpreted’. There are facts that exist even when we don’t see them. The whole morning we did nothing but try to find this reality behind the notes. We never said: "You have to do it like this!" Instead: You have to discover what exists, beyond ourselves. I could explain to him: "The phrase is like this", and he would imitate Celibidache. – I insist that he himself finds out that he went beyond the notes without making them his own, without humanizing them.

What is the sense of a musical phrase? "Tata hee hoo hii doo pff." Why is this senseless? Because the beginning has no relation to the end. A sequence of tones follows a structure which finally connects the beginning with the end. When do I know that a piece has come to its end? I know it when the end is in the beginning. When the end keeps what the beginning promised. Continuity doesn’t mean: to go from one moment to the next, but: after going through many moments to experience timelessness. That is where beginning and end live together: in the now. What is required to experience any structure as a whole? The absolute interrelation between the individual parts. When I don’t feel the parts but the whole, what did my mind do? Integrate.

What did I learn from Furtwängler? One idea which opened all doors for my whole life and for all my studies: When the young Celibidache asked him: "Maestro, this transition in this Bruckner symphony – how fast is it? What do you beat there?" "What do you mean by 'how fast'? he replied. It depends on what it sounds like! When it sounds rich and deep I get slower, when it sounds dry and brittle I have to get faster." He adjusts according to what he actually hears! According to the actual result, and not to a theory! "92 beats per minute." – What does ‘92’ mean in the Berlin Philharmonic, and what does it mean in Munich or in Vienna? What nonsense! Each concerthall, each piece and each movement has its individual tempo which represents a unique situation.

Something starts to move, but you don’t notice that it is moving in time. If anyone has the feeling it is either too long or too short, he is already out of the music. Here you can somehow live beyond time. In this sense music has no duration in time. In any normal concert you are out of it all the time. In a hundred concerts a year, if there are three where you somehow stayed with it – that would be a lot.

„Celibidache Rehearses Bruckner’s Ninth“ – Director’s Notes

By Jan Schmidt-Garre

Many years after completing my major film about Sergiu Celibidache I was looking through the rolls of film I had not used when, amongst the uncut material, I was fascinated to discover some footage of the old Celibidache rehearsing Bruckner’s Ninth. My immediate thought was that if a viewer were zapping around and came across this expressive face reflecting every nuance of the music, he or she would stay with it for minutes on end. But as soon as the usual shot of a particular musician playing came up, I would have lost her. „Ok, a cultural film”, she would say to herself, and would continue zapping through the programmes. So I decided to try to use the material to create a film that would retain the intensity of this great man and, while the orchestra was playing, would concentrate on Celibidache’s face – the musicians would only feature during the verbal dialogue. In the cutting room it became clear that this in no way means a downgrading of the importance of the musicians. What it does is reflect the division of labour between orchestra and conductor. Celibidache himself described the conductor as a relatively late historical phenomenon – a “dubious figure” who does not make music himself but rather uses the expressivity of his hands, arms and face to seduce others into making music. His face is the screen onto which the music is projected.

Celibidache’s Presence of Mind

Obituary by Jan Schmidt-Garre, first published in Die Wochenpost, 17.8.1996

German version on waahr.de

No one brought so little baggage on to the platform. He did not even have his baton with him – it was left on the leader’s desk by the orchestra assistant. And of course he did not carry a score with him either – except in his head. And even there he did not perceive it as baggage, as a burden from the past which he brought to the concert with him, but as what he needed to exercise his best talent: his presence of mind. We learned as his students through molecular exercises that this paradox is possible: it is possible to internalize a score, it is not a lifeless entity in the memory but a living structure. He would ask someone to write a random 12-tone row on the blackboard, the most desolate phrase that one could imagine. And then the process of humanization began, the search for its innate order. How is it divided? How can it be phrased? How can it be conducted? Where are its joints? One student after another would go to the piano and try his luck. Celibidache could be cutting and sarcastic if you didn’t have it right; he could be a disheartening teacher. Finally someone would succeed, and suddenly this lifeless, amorphous material sprang to life and assumed shape. And then during the break on the giant stairs of the University of Mainz, the stairs that the fragile maestro mounted every morning, I suddenly found myself whistling something as easily as if it were by Schubert: the 12-tone row.

The rehearsal begins. The cellos and basses play the first phrase of the Kyrie from Bruckner’s Mass in F Minor; the violas take over, then the violins. A giant, giant body begins to take shape, infinitely larger than the 12-tone row, but structurally similar, just as rounded and closed. And then all of a sudden: "No! That’s mambo!" The violins were a little blurred just before entry of the chorus. Celibidache’s disappointed face has looked up at me a hundred times from the editing table, with its pain at the impairment of a well-formed shape, wounding the very man who has keenly perceived and mentally projected this shape. This inaccessible, solitary emperor had the gift of giving himself completely to the vibrant, living sonorities. The man who did not care if he was loved or liked by all, who maintained a distance even in laughter, this man was completely naked, exposed and infinitely vulnerable at the podium. And the results were accordingly bounteous when everything was right. The music emanated from a giant personality capable of opening a vast number of sluit gates. His Zen ideal of opening and emptying himself to the music was misunderstood by many students as a state of poverty, thin-blooded and lacking in substance, but no: this colossus opened himself up – when it worked, that is to say two or three times in a hundred concerts, as he used to say – and let us participate in a huge surge of energy.

"What is your name? Do you smoke? Never touch a cigarette!" That was the initiation for countless students from throughout the world when he taught – gratuitously a rule. Maybe he also said, "you have to live with me for a few years", and then you were under his spell. From then on life was divided into right and wrong. His personality was oppressive for many, and he was never reserved in that respect. Skeptics often described him as a guru, and there were certain parallels that we his students couldn’t deny. But is it possible for someone with vision, a true spiritual master, to be reserved?

Celibidache’s rehearsals were never hypothetical; every rehearsal was the real thing, presenting the greatest possible challenge to each musician to submerse himself in every piece as if for the first time, to be driven on by what had been heard and experienced. All or nothing: as long as he didn’t interrupt, everything was fine. It wasn’t the little inaccuracies that made him stop, but breaks in the flow of music, for example, in the Benedictus of the Mass in F Minor, if the violins didn’t listen to the flute solo, didn’t pick up its phrasing. Celibidache angrily corrected the violins and then gently turned to the flutes: "Maxi, breathe in much more calmly. We are alone." The flutist should follow the organic flow of his breathing, the human scale. We are alone? Two human beings make music with one another, listen to one another, jointly give shape to a work of art, unaffected by the external demands of a metronome. But physically, too, they are alone: two hundred colleagues in orchestra and choir are obliterated in this intimate moment shared by flute and conductor. Celibidache could command such intimacy anywhere, at anytime.

It was his presence of mind that rewarded him with such a long life, that gave him renewed life and energy for new rehearsals and concerts after every illness. Once on the platform there were no worries about the next diagnosis, no fears about the coming night – here there was only the pure moment, which he was never ready "to sacrifice to the future" (to quote Horkheimer): the sound here and now. The mystic "instant". In a completely unsentimental, objective sense, making music was a religious act for Celibidache. No baggage, no memories, no outwitting transitoriness with gramophone records – he could and would not rest on anything: each rehearsal was a clean state, always new, always claiming the whole person. In this way he embodied the ideal of the conductor and artist and human being with a radicalism shared by few in the 20th century: to live in the present.

(Jan Schmidt-Garre studied with Celibidache before shooting his film "Celibidache – You Don't Do Anything – You Let it Evolve". Celibidache died in 1996.)