Furtwängler’s Love

Facts

Film Essay, 70 min, 2004Directed by Jan Schmidt-Garre

In collaboration with Georg Albrecht Eckle

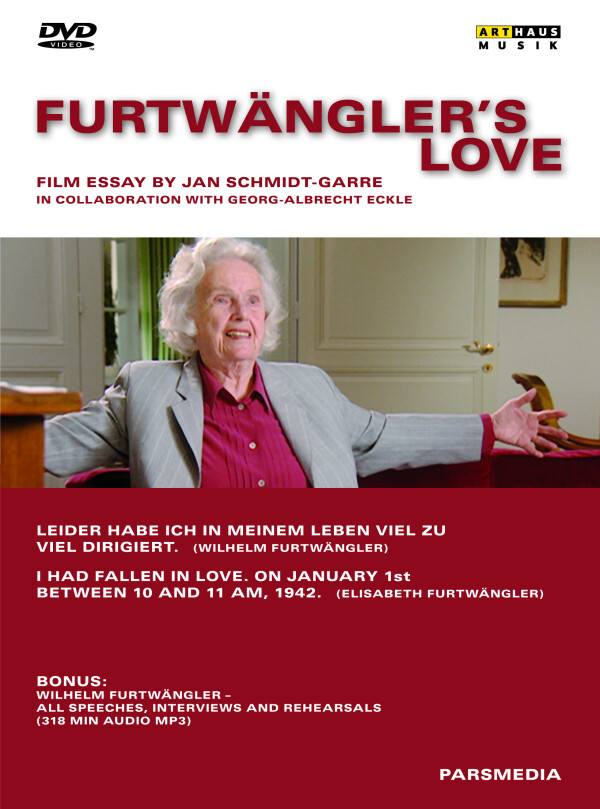

Furtwängler’s Love – above all, his wife Elisabeth, with whom he was happily married from 1943 until his death in 1954.

Furtwängler’s Love – conducting, the way in which he publicly expressed his love of music.

Furtwängler’s Love – composing, a secret passion that he regarded as the central focus of his existence.

Furtwängler’s Love – the aesthetic principle of Furtwängler the theoretician, for whom every artistic expression was an act of love.

Featuring Elisabeth Furtwängler, Ingolf Turban, Roberto Saccà and Frederik Malmqvist

Cinematography: Thomas Bresinsky

Editors: Peter Przygodda, Wolfgang Weigl

In co-production with MTV, NRK, ORF, SF, SVT, TSI, and YLE

Supported by Media+

Press

Statement of the Jury at Golden Prague, Mai 2004 (Czech Crystal special mention)

A warm and personal film that beautifully lives up to its title.

Statement der Jury des Golden Prague, Mai 2004

... Die ganze siebenköpfige Jury war begeistert von der persönlichen, warmherzigen Atmosphäre des Films, dessen Herzstück natürlich das wunderbare Interview mit der Witwe Furtwänglers ist. Unter allen Filmen im hochkarätigen Wettbewerb war "Furtwängler’s Love" eindeutig der persönlichste: nicht nur, weil er aus der subjektiven Perspektive erzählt, sondern weil er einen ganz eigenen, nicht von "objektivem" Archivmaterial verstellten Zugang zur Persönlichkeit Furtwänglers findet. Beeindruckend fanden wir, dass der Film von vornherein auf dokumentarische Chronologie und Vollständigkeit verzichte. "Furtwängler’s Love" läßt sich Zeit und entwickelt seine Dramaturgie ganz aus der Nähe und der Atmosphäre der menschlichen Begegnung; das gibt ihm seinen eigenen Atem und macht ihn so bewegend. Ein sehr sehr schöner Film, zu dem ich – auch abseits von der Auszeichnung – ganz herzlich gratuliere.

"Beeindruckend fanden wir, dass der Film von vornherein auf dokumentarische Chronologie und Vollständigkeit verzichtete. "Furtwängler’s Love" läßt sich Zeit und entwickelt seine Dramaturgie ganz aus der Nähe und der Atmosphäre der menschlichen Begegnung, das gibt ihm seinen eigenen Atem und macht ihn so bewegend." (Thomas Beck, Golden Praque Jury Mitglied) Ein filmischer Essay von Jan Schmidt-Garre über Wilhelm Furtwängler, den großen Dirigenten, den engagierten Komponisten und den liebenden Partner. Seine Witwe, Elisabeth Furtwängler erzählte 2004 in privater Atmosphäre, Unterhaltsames, Nachdenkliches und Intimes, Details aus einem gemeinsamen Leben vom ersten Kennenlernen bis zum letzten Kuß. Ein ganz eigener, nicht von "objektivem" Archivmaterial verstellter Zugang zur Persönlichkeit Furtwänglers.

Süddeutsche Zeitung, 15.7.04

Ein Leben, zwei Lieben

Wilhelm Furtwängler kannte keine Werktreue, Tempoangaben waren ihm fremd. "Es gibt nur ein Tempo, und das ist das Richtige", sagte er einmal. 2004 jährt sich der Todestag des Dirigenten, der dem Orchester seinen Willen nicht allein durch übliches Taktschlagen, sondern vor allem durch expressive Gestik zu vermitteln suchte, zum 50. Mal. Der Filmessay "Furtwänglers Liebe" blickt zurück auf das Leben des Dirigenten und Komponisten und stellt die verschiedenen Bedeutungen des Wortes "Liebe" in Furtwänglers Leben vor. Furtwängler selbst definierte die Liebe einmal so: "Sich-Einstellen heißt Liebe. Sie ist das Gegenteil vom Abschätzen, vom Vergleichen. Sie sieht das Unvergeleichbare, Einzigartige." Da war natürlich die Liebe zur Musik, die er als Dirigent öffentlich ausdrückte und als Komponist als geheime Leidenschaft pflegte. Der Film verzichtet allerdings auf Rückblicke, nur zweimal taucht blitzartig ein historischer Filmausschnitt auf. Aus der Gegenwart wollte Drehbuch-Autor und Regisseur Jan Schmidt-Garre das Wirken Furtwänglers beleuchten. So erklingen die Violinsonaten, frühe Klavierstücke und -lieder – gespielt von Ingolf Turban – bei einem Fest in Furtwänglers Haus, an seinem Flügel, unter seinem Kokoschka-Portrait. Elisabeth, seine Ehefrau von 1943 bis 1954, gewährt dem Zuschauer Einblicke in ihr Haus am Genfer See – und in ihr Herz. Die heute 93-Jährige erzählt mit Humor und Leidenschaft ihre Liebesgeschichte, von der ersten Begegnung über den ersten Kuss bis zu Furtwänglers Tod. Furtwängler selbst kommt in Radio-Interviews und Vorträgen zu Wort, auf Interviews mit anderen heute 90-jährigen Zeitzeugen wurde bewußt verzichtet.

Anja-Rosa Thöming, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 7. 6. 2008

Alterslos – Furtwänglers Liebe, mit viel Poesie dokumentiert: Jemand fährt Zug und studiert eine Partitur. Eine alterslose Männerhand mit breitem Ehering, in hellem Mantelärmel, schreibt mit Bleistift Anmerkungen zwischen die Noten. Draußen gleitet ein Nadelwald vorbei. Dazu ertönen Hörner und weiche Streicher, „Freischütz“-Ouvertüre. „Ein Werk über die Liebe, wie kaum ein zweites“, sagt Wilhelm Furtwänglers Stimme aus dem Off – Zitat aus der Rede zur Salzburger „Freischütz“-Produktion aus seinem letzten Lebensjahr, 1954. Dann überquert der Zug eine stark befahrene Autobahn. Die Sequenz wird nicht aus dem Film eleminiert. Die Verfremdung durch Vermischung der Zeiten bleibt bestehen. Jan Schmidt-Garres Dokumentarfilm über den liebenden Furtwängler hat Mut zu Poesie, aber kitschig wird er nicht. Davor schützt ihn seine Protagonisten, Furtwänglers Frau Elisabeth. Wann immer sie über die erste Umarmung, die Schüchternheit, die Frauenleidenschaft von „Fu“ spricht, bezaubert sie den Zuschauer durch unsentimentalen Charme. Sie ist der Typ eines Berliner Bürgertums des Vorkriegs, schlagfertig und gebildet. Wenn die eigenen Kompositionen Furtwänglers, der sich selbst immer als Zufallsdirigent sah, gespielt werden, hört sie mit ungekünsteltem Ausdruck.

Henry Fogel, Fanfare Magazine, September/Oktober 2008

This is a very peculiar, but appealing film that will be of interest to anyone interested in Wilhelm Furtwängler. At the center of the film is the remarkable widow of the conductor, Elisabeth, who was in her early nineties when this film was made. The film purports to explore Furtwängler’s loves – music and Elisabeth – and does so in a very touching, human way. Furtwängler’s Love is described as a “film essay,” and it is a deeply personal and revealing portrayal of both the artist and the man. Elisabeth is remarkably frank, about falling in love with him at a time he was dating her sister, about his “harem” and his many illegitimate children, and about how deeply she was in love with him and he with her. Perhaps most moving is her description of his final days in 1954, when he knew he was dying and, in fact, was ready to die.

At the same time, the film explores, through Furtwängler’s own words, his feelings about music – and about composing as well as conducting. It makes clear that he (in much the same way as Leonard Bernstein) wished to be remembered as a composer rather than a conductor. I found the personal openness and conversational approach taken with Elisabeth to be both involving and moving, and I would recommend the film to anyone with an interest in Furtwängler, and this period in German history.

Der Neue Merker, 26. 3. 2008

Furtwänglers Liebe lässt sich Zeit und entwickelt seine Dramaturgie ganz aus der Nähe und der Atmosphäre der menschlichen Begegnung; das gibt ihm seinen eigenen Atem und macht ihn so bewegend. Ein sehr schöner Film, der zugleich ein Stück deutscher Geschichte, hier jedoch ganz persönlich gefärbt, dem heutigen Interessenten nahe bringt.

Awards

Golden Prague

Releases

On DVD with Arthaus Musik. 318 minutes of speeches, interviews and rehearsals with Furtwängler added as an audio bonus file:

Texts

Wilhelm Furtwängler: On Love and Music

The Furtwängler Love Letters

Is a Celibidachian allowed to love Currentzis?

Wilhelm Furtwängler: On Love and Music

Love

One has to immerse oneself in a work of art, it’s a self-contained world, a world unto itself. This process is called love. It is the opposite of evaluating or comparing. It only sees the incomparable, the unique. It is this love, provoked by the work again and again, that enables us to grasp the work as a whole. And the whole is nothing other than love. Every part can be grasped by the intellect, but the whole can only be understood with this kind of love.

Cadenza

The basis of the tonality is the cadenza. A certain space is encompassed by its simplest steps, one to the dominant and then to the sub-dominant and finally back to the tonic. These steps not only make a connection between one chord and the adjacent one but also – and this is crucial – they also create a greater, superior context that connects together all the links in the cadenza from its starting-off point to its end. This superior context, this space that the cadenza creates, is nothing less than the decisive element: the music can take shape, it has found a point from which it can depart and an end that it can reach. A fugue such as Bach wrote or a movement from a symphony such as Beethoven wrote represent literally a cadenza extended into gigantic proportions.

Interpretation

Thus a piece of tonal music offers something like a view of the sea: there are smaller waves on top of big ones, and smaller ones again on top of them, and so on. The wave is here the same as the tension in a cadenza, large ones and ever-smaller ones laid on top of one another. We are therefore dealing here with a system of independent forces that take their effect independently of our desires and wishes. It is not until our desire for expression becomes one with the desire for expression of these forces that the work of art can arise.

Atonality

Accompanying an atonal musician hand-in-hand is like going through a thick forest. Along the path, weird and wonderful flowers and plants draw our attention and one does not know oneself where one has come from or where one is going. The listener is gripped by the feeling of being exposed to the power of elemental existence. There is admittedly no denying that a certain note has thus been struck in the modern human being’s feeling for life.

Tonality

In contrast to that the cadenza arises in tonal music on the firm foundations of the triad. The tension grows out of the release of tension in order to grasp the diversity of life’s forms and ultimately, according to the law that governs it, to return to the starting-off point, the so-called tonic. The more tranquil and complete the release of tension is the more powerful are the tensions that become possible on its basis. Indeed, it is only through the corresponding release of tension that must precede it that any kind of tension is possible in the first place and can be recovered afterwards. Every great piece of tonal music, therefore, despite all the excitement that can be driven to the limit of human comprehension, exudes a deep and unshakeable tranquillity that permeates everything and everyone like a memory of the majesty of God.

(Compiled by Jan Schmidt-Garre from Furtwängler’s essays and letters)

The Furtwängler Love Letters

Elisabeth to Wilhelm, 9. 1. 1942

Dear Fu,

This is the only letter I am going to write to you. I will not see you again until I am sure in my mind that we can be friends without endangering the love between you and Maria. And Fu – if we ever see each other again, then please never take me in your arms, however much you would like to – or however lovingly I may look at you.

If you agree with my letter, then don’t answer. And if you do not agree – then definitely do not reply.

Your Elisabeth

Wilhelm to Elisabeth, 3. 2. 1942

Dearest Elisabeth,

I have been pondering over everything and am now quite clear in my mind about it all. In everything that you have, do, and say – and how you look – you are the sweetest picture of femininity I have ever come across. Even if I have at times been egoistical and irresponsible in my life, I cannot behave in such a way towards you – not in the slightest.

I will arrange the journey so that I visit my mother in Heidelberg and then go on to Frankfurt, perhaps in the morning, so we can meet there at midday. Or can you come to Heidelberg for the night? Things would be quieter there – and there is also that lovely peaceful hotel.

You can’t imagine how I am counting the days, my dear!

Farewell

W.

Elisabeth to Wilhelm, 16. 4. 1942

My dear, if only you could draw as much strength from my love for you as I do from your love for me. But it is not longer a question of mine or yours – it is our love. I used to think it would perhaps be a wonderful experience and would then end. But this is merely a blissful beginning, and so much happiness lies before us. Do you feel the same? You have made me so happy.

Your E.

Wilhelm to Elisabeth, 16. 4. 1942

Dearest, I feel I am living in a dream. I constantly see before me your eyes, your smile, your person. I have truly lost my heart – lost it to you. I am thinking of you, my darling, my dearest, sweet joy. W.

Wilhelm to Elisabeth, 26. 4. 1942

Dearest, it is not just your mouth, your eyes, your cheeks that I would like to kiss and caress, but also your neck, your shoulders and your beautiful arms. Then your sweet, sweet, sweet breasts – both of them, one after the other. But even that is not enough. I want to kiss and caress everything – your entire body, immerse myself in your closeness and then once more take you into my arms and press you to me, again and again.

Goodbye! W.

Elisabeth to Wilhelm, 4. 2. 1945

Dearest,

Our child is lying next to me in his cot, snuffling happily, replete after his first feed. I have simply written ‘our child’, but these words mean so much to me! I sometimes repeat them softly when I hold him in my arms and am overcome by a sweet heaviness. He is alive and is a living, warm child. So it is true that I am your wife, that you have held me in your arms and I have melted in the sweetness of your embrace.

Your Elisabeth

Wilhelm to Elisabeth, 21. 2. 1949

Dearest, it struck me how true it is what Wagner says about the redemption of man by the pure, unwavering love of a woman. It is the most precious thing on earth, and I never knew it. But now I know it – late on, but not too late. Oh my dearest, everything that I still have and experience in my life strengthens me in this one belief: I love you! W.

Is a Celibidachian allowed to love Currentzis?

by Jan Schmidt-Garre, first published in Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, 20.8.2017

(German version on waahr.de)

„How was the super crazy Currentzis?“ my friend Christoph asked by e-mail. I had told him that I was going to the premiere of Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito at the Salzburg Festival, conducted by Teodor Currentzis. I hesitated to answer. The fact that I had liked it was kind of embarrassing, especially in front of Christoph. We had both studied with the conductor Sergiu Celibidache, Christoph much more intensively than I did, but I had also become very close to Celibidache because I had made a film about him over almost four years. And I knew, of course, what Celibidache would have shouted in that Titus, every few bars, „Locally thought!“ That was one of the worst judgments. It meant that the musicians had celebrated a beautiful passage without putting it in the context of the whole – and context was all that mattered. Then in the evening I gave myself a jolt. One does have a duty to confess, I thought, and wrote Christoph briefly, „It was great!“

To entrust Currentzis, of all people, with his first opera premiere was a real coup for the new artistic director of the Salzburg Festival, Markus Hinterhäuser, a manifesto. And he engaged Currentzis not with the Vienna Philharmonic, the Festival’s traditional orchestra, but with the Russian orchestra MusicAeterna, which Currentzis had founded thirteen years ago in Novosibirsk as a baroque ensemble and then developed into a major symphony orchestra in the city of Perm. The recordings of Mozart’s Figaro, Così and Don Giovanni that made Currentzis famous in the West were produced in the Perm Opera House. With the Salzburg premiere, he has now arrived in the „royal class,“ as the German newspaper Weltwrote; for Süddeutsche Zeitung, he is currently „radically the best Mozart conductor.“

Why did I find it so difficult to judge, why couldn’t I just write down a superlative, why the dramatic talk of confession? Because the way Currentzis makes music is not only a little different from what Celibidache did, because he does not only play a little faster, sharper, rougher, like many conductors today, but because a paradigm shift is taking place here. In the old paradigm, for which Celibidache is not the only one, of course, but, well: paradigmatic, the unity of the artistic form was the highest goal. A musical phrase is heard, the next one answers it, the proceedings open up again, and again there is a response. One plus one becomes two, two plus two becomes four, and so on until the climax, after which the forces reverse and return to the calm of the beginning, so that the whole process is but a single reaching out and catching up again, a single movement of expansion and compression, a single breath that can extend – say in the slow movement of Bruckner’s Eighth – over an incredible thirty-five minutes. Viewed from the outside, as Celibidache would immediately object, because from the inside, from the experience, there is no temporal duration, all this happens in the now. What Celibidache expressed in the seductive image that the end is already contained in the beginning.

For Celibidache, as for his teacher Furtwängler, this idea was indissolubly linked to tonality. „On the firm foundations of the triad,“ Furtwängler wrote, „the cadence arises in tonal music. Out of the release of tension the tension grows to grasp the multiformity of life and finally – according to the law according to which it started – to return to the starting point, to the so-called tonic. Every great piece of tonal music, therefore, despite all the excitement that can be driven to the limit of human comprehension, exudes a deep and unshakeable tranquillity that permeates everything and everyone like a memory of the majesty of God.“

Now, what does Titus sound like with Currentzis? Rugged, wild, archaic. Utterly strange and new. On a small scale, of course, the complementary phrases also exist with him; a musical person cannot help but feel complementary in this way. But then suddenly there are contrasts of a harshness that can no longer be resolved with the available musical material. Dynamic contrasts from the most extreme pianissimo I have ever heard to the strongest fortissimo. Entrancing caesurae in which the world holds its breath, but also abysses in which it loses itself.

„At the hand of the atonal musician,“ says Furtwängler, and one thinks he is talking about the Salzburg Titus, „one walks as through a dense forest. Along the path, weird and wonderful flowers and plants draw our attention and one does not know oneself where one has come from or where one is going. The listener is gripped by the feeling of being exposed to the power of elemental existence.“ Seventy years ago, Furtwängler was already well aware of the fascination that could emanate from this strange world: „There is admittedly no denying that a certain note has thus been struck in the modern man’s feeling for life.”

According to Thomas S. Kuhn, a new scientific paradigm emerges when the old one is in crisis. Anomalies occur that can only be explained in a makeshift way, and finally, somewhere in the world, „extraordinary research“ begins that leads to the new paradigm. Talk of the crisis of classical music began around the time of Furtwängler’s death, in the 1950s. Today, the average intellectual no longer considers it a lack of education not to know what a liberating experience a coda can be, in which the composer, on the last bars of the piece, with dwindling strength, gains some more time, through small unassuming motions in the musical material. And while the intellectual would be uncomfortable not being able to say anything about the golden ratio or about the form of the sonnet, he does not know how the dominant relates to the tonic – and what that sounds like.

When Teodor Currentzis works out the works of Mozart, Rameau, Tchaikovsky or Shostakovich with a group of friends in the foothills of the Urals, with no time constraints, no obligation to perform, no financial pressure, this can certainly be called „extraordinary research. « » You can’t gather partisans in the capital,“ Currentzis says, „you gather them in other places, somewhere in the woods.“ The new paradigm that emerged from this underground is now conquering the world from Salzburg.

And Currentzis himself is very aware that this is a new paradigm. „Every person,“ he says, „has a Dionysian and an Apollonian side. Classical music has dealt only with the second. The Dionysian is the wild, unadorned side of the subconscious, where its own algebra and geometry rule. It leads to drunkenness and ecstasy when it comes into contact with the outer world. When was the last time you experienced Dionysian ecstasy in a concert hall?“

The musicians of the Apollonian paradigm wanted to convince. Currentzis wants to persuade and overwhelm. To this end, he is willing to use any means, including extra-musical ones. At the beginning of his concerts with the phenomenal MusicAeterna Choir, he completely darkens the hall. A distant chant rises from nowhere. It brightens a bit, and the black-clad Currentzis slowly strides to the podium and takes over. At the end of the intermission of Titus, he mingles with the choir singers and lays flowers of mourning on the stage for the shot emperor Tito. For him, theater and music are one, and significantly, in Titus it is the accompagnati that are particularly gripping: the most impure music of the opera, the recitatives with orchestra, completely committed to action and emotional dynamics, close to stage music – and far from the closed form.

Much is lost, and perhaps one must have inhaled the old paradigm as strongly as Christoph and I did under Celibidache’s influence to feel the farewell so painfully. But a very great deal is also gained: a radically contemporary world that makes one wide awake and drunk at the same time. Currentzis reaches the „modern man“ of whom Furtwängler spoke more directly than almost any other musician today. In 2005, then still in Novosibirsk, English critic Peter Culshaw asked him if he had a mission. „I will save classical music. Give me ten years, and you’ll see!“