Celibidache – You Don’t Want Anything – You Let it Evolve

Facts

Music Documentary, 100 min, 1992Directed by Jan Schmidt-Garre

A feature length portrait of conductor Sergiu Celibidache, a phenomenon in the world of classical music. Four years in the making, director Jan Schmidt-Garre collaborated closely with the charismatic musical director of the Munich Philharmonic and the result is an exceptional look at an artistic and intellectual giant as well as a passionate journey into the creative process.

Cinematography: Karl Walter Lindenlaub, Diethard Prengel

Sound recording: Nina Ergang, Edith Eisenstecken

Associate producers: Jakob Claussen, Nicole Houwer, Carsten Lorenz, Robert Knon

A co-production with ZDF and ARTE/ZDF

Supported by Kuratorium junger deutscher Film, Bundesministerium des Innern and FFF

Press

Wolfgang Schreiber, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Jul. 7, 1992

Surprising and at the same time illuminating: director Jan Schmidt-Garre has created a film that exceeds the considerable length of hundred minutes employing just a single theme, the patient observation of conductor Sergiu Celibidache during the creation of, during his work on music. The sensitive conductor, perhaps more hypersensitive than any other artist when it comes to disturbing his work, has let no one else approach him so closely. And: finally a portrayal of a musician without the family portrait at the end, without hackneyed phrases and foolish, sentimental remarks, without the typical attempts to expose indiscretions. » You don’t do anything, you just let it evolve «, the film’s subtitle is a citation from the philosopher of music Celibidache. Schmidt-Garre accompanied and observed the maestro at his rehearsals with the Munich Philharmonic and with the Schleswig-Holstein Youth Orchestra over the course of years. He succeeded in capturing the intensity, the concentration, as well as the human compassion with which Celibidache led his orchestral and choral rehearsals. And with which the conductor, true to his maxim that teaching is the most important human act, instructs his students about music and its rules. Whether at the University of Mainz or at a mill in France during his vacation (where he had taken a whole chamber orchestra from Italy), Celibidache teaches with wisdom, humor and infinite competence. Has the technique of conducting ever been explained so humanly? Or the difference between tension and intensity? ... Schmidt-Garre has mastered the art of observing without intruding, as well as the art of discriminating commentary, thereby opening the way for charming episodes, such as » Celi’s « meetings with old friends on his travels to Romania and Israel. It was more than obvious: Celibidache is not only greatly admired, he is also loved by many.

Klaus Bennert, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Mar. 21/22, 1992

Schmidt-Garres Film nähert sich dem Maestro mit unverhohlener Verehrung; daß dennoch das Bild eines genialisch Schwierigen mit all seinen Widersprüchlichkeiten entstanden ist, wird dessen Naturell durchaus gerecht.

Hans Göhl, Münchner Merkur, Feb. 11, 1992

Schmidt-Garre hat die Suggestivkraft erhöht, indem er auf alle "filmischen" Mätzchen verzichtete und sein Material sorgsam und ruhig anordnete. Er zeigt mit diesem Film ausgesprochenes Dokumentations-Talent.

Paula Linhart, filmdienst, Mar.31, 1992

Der Maestro offenbart sich in diesem Dokumentarfilm in einer Weise, die einer persönlichen Begegnung gleichkommt und die besondere Art und Intensität seines musikalischen Kunstverstandes faszinierend im Werk offenbart. Obwohl teils längere, teils kürzere Schnitte das Szenarium auf die verschiedenen Schauplätze und Aktivitäten ohne chronologische Einordnung verteilen, zerfällt der Film nicht in Abschnitte, sondern verknüpft sie zur übereinstimmenden Ganzheit. Er hält die Spannung trotz seiner Länge bis zuletzt durch.

Jan Schmidt-Garre heftete sich drei Jahre mit seinem Team (sehr gute Tonübertragungen) an Celibidaches Fersen. Schmidt-Garres Bewunderung für den Dirigenten ist unverkennbar, doch hievt er ihn nicht aufs Podest erhabener Distanz. Der Film springt mitten hinein in das Erlebnis Musik und seine Faszination, und wenn er aufhört, nimmt man es mit nach Hause: als Dauergeschenk.

Regina Leistner, Berliner Morgenpost, Apr. 12, 1992

Sehr liebevoll und sensibel produzierter Dokumentarfilm, ein Muß für jeden Musikfreund.

Albrecht Dümling, Tagesspiegel, Berlin, Apr. 13, 1992

Man sieht, wie Musik entsteht – nach Aussage des Dirigenten ein Mysterium, eine Suche nach Wahrheit, die sich allen Definitionsversuchen entzieht. Musizieren ist für ihn das Eintauchen in eine Welt der Zeitlosigkeit, der Ewigkeit. Wie geduldig der Dirigent mit dem Chor und den Solisten umgeht, wie klug im Film dann die verschiedenen Probenphasen aneinandergeschnitten sind, das ist hörens- und sehenswert.

Carla Rhode, Tagesspiegel, Berlin, June 6, 1992

Ein eindrucksvolles, menschlich sehr anrührendes Porträt des Dirigenten, ganz aus der musikalischen Praxis entworfen.

Volker Hagedorn, Hannoversche Allgemeine, June 22, 1992

Einmal läßt Celibidache junge Musiker ohne Noten spielen. Irgendwas, drauflos. Nur auf seine Bewegungen sollen sie reagieren. Und diese Bewegungen sind so differenziert und unmißverständlich, daß ein strukturiertes Klanggebilde entsteht. Wer schon immer wissen wollte, wozu man eigentlich Dirigenten braucht, sollte diesen Film sehen. Wer schon immer wissen wollte, was Celibidache zum Frühstück ißt, wird es nicht erfahren.

Andreas Obst, Frankfurter Allgemeine, Jul. 7, 1992

Der Film ist wie sein Gegenstand: geschichtslos, allein dem Augenblick verpflichtet, nachdenklich, verstörend, provozierend. Es ist ein bemerkenswerter Film über den heute achtzigjährigen Pult-Star, der sich in der Position des grüblerischen Anti-Stars gefällt, selten nur Interviews gibt, tatsächlich jedoch zu dozieren liebt. Man wird süchtig nach Celibidache in diesem Film, der selten etwas anderes zeigt als das von Falten und Narben zerfurchte und von weißen, kinnlangen Strähnen, wie der greise Liszt sie trug, umrahmte Gesicht, oder man wendet sich ab, um nie mehr hinzusehen…

Peter Michael, Wiesbadener Kurier, Jul. 7, 1992

Keine der üblichen Huldigungen, sondern eher ein analytischer Essay.

Südkurier, Jul. 7, 1992

Bei Proben, Diskussionen und Dirigierseminaren war der Regisseur mit den wunderbar beobachtenden Kameramännern Karl Walter Lindenlaub und Diethard Prengel zugegen. Das Schwierigste hat er vollbracht, das Leichteste vermieden: Statt "Standing Ovations" – Abfilmerei, glanzvoller Bilderbiographie und Fragen in Kotaurhetorik – hat Schmidt-Garre zugehört und hingeschaut.

Wilhelm Roth, epd Kirche und Rundfunk, Jul. 11, 1992

Bei aller Einseitigkeit: Jan Schmidt-Garres "Celibidache" ist ein Film, der schon wegen seiner Einmaligkeit in die Fernseh- und Musikgeschichte eingehen wird. Von wieviel Fernsehfilmen kann man das sagen?

Dieter Borchmeyer, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Oct. 20, 1995

Dem Regisseur und Philosophen gelingt es, die bizarre Persönlichkeit dieses Dirigenten, seine magische, allzuoft freilich despotisch-knechtende Wirkung auf Musiker und junge Menschen, aber eben auch sein unverwechselbares Musikerprofil nach allen Seiten auszuleuchten. Zu irgendwelchen Sottisen gab Schmidt-Garre Celi keine Gelegenheit, dafür entlockte er ihm eine Reihe von substantiellen musikalisch-praktischen Äußerungen, welche die Faszination des Pult-Gurus begreifen lassen.

Jens Hagestedt, Szene Hamburg, Aug. 1993

Schmidt-Garre zeigt Celibidache bei der Probenarbeit mit verschiedenen Ensembles und, besonders eindrucksvoll, auf den verschiedenen Gebieten seiner weitgespannten Lehrtätigkeit, in Theorieseminaren und bei der praktischen Unterweisung. Wie eine Sinuskurve geht die Rhythmik des eigentümlichen, problematischen Beziehungsverhaltens Celibidaches durch diesen Film: Immer wieder zeigt sich die ungewöhnliche Fähigkeit des Dirigenten, Nähe zuzulassen, immer wieder wird deutlich, daß sie die Unterwerfung des Anderen zur Voraussetzung hat. Ein anrührendes, nachdenklich stimmendes Dokument.

Jürgen Seeger, Bayerischer Rundfunk, Dec 22, 1992

Man will nichts – man läßt es entstehen – der Titel weist auf den geistigen Hintergrund des Zen-Buddhisten Celibidache hin, der die Kunst des Bogenschießens auf musikalische Weise pflegt. Schmidt-Garre rückt dem Dirigenten auf den Leib, bewahrt dabei aber auf angenehme Weise Distanz. Ein anregender und im besten Sinne lehrreicher Dokumentarfilm.

Dorothea Zweipfennig, Der neue Merker, Wien, Mar. 1993

Nichts wurde gestellt. “Celi en nature”. Ein wichtiges Dokument.

Gong, Jul. 25, 1992

Reserviert bis unwirsch gegenüber Fans und Journalisten, so war man Maestro Celibidache gewohnt – bis zu diesem Porträt. Aber wer intelligente Fragen stellt und das Wesentliche, die Musik, in den Mittelpunkt stellt, kommt bei "Celi" offensichtlich gut an. Bis zur Filigranarbeit des Taktschlagens erläuterte er Jan Schmidt-Garre sein Handwerk, zeigte den mühsamen Weg der Proben bis zum seltenen Moment einer für ihn perfekten Passage. Keine oberflächlichen Stimmungsbilder, sondern ein spannendes, leidenschaftliches Porträt musikalischen Gestaltungswillens.

Awards

Silver Medal at the Chicago International Film Festival

Nominated fort he German Film Prize

Midem Classical Award 2010

Additional

Poster "Celibidache"

The treatment, meticulously designed by Jan Schmidt-Garre, then a student at Film Academy.

Invitation to a screening with discussion at the Catholic Academy, Munich

Old advertising leaflet

Quotes

You can’t do anything other than let it happen. You just let it evolve. You don’t do anything yourself. All you do is make sure that nothing disturbs this wonderful creation in any way. You are extremely active and at the same time extremely passive. You don’t want anything; you let it evolve.

A rehearsal is not music. A rehearsal is the sum of uncountable ‘nos’. "Not too far, not too loud, not above the bassoon, not so dull." How many ‘nos’ are there? Billions. And how many ‘yeses’? Just one.

That is the complete training. You have to do at your seats what I am doing at mine. You have to conduct with me. We react spontaneously to what we hear, that is, functionally, as is necessary. Not "this is marked piano, this is marked forte…" – no one is interested in that.

I don’t know if that gives you an idea of what I would like: to emanate from what already exists. The way oil spreads, becoming wider and wider and wider. Not so pointed. Those are notes, but not yet music.

What is the ‘interpretation’ in what we are doing here? It's nothing else but finding out what the composer had in mind. He starts from an experience and looks for the notes. We start with the notes to come to his experience.

When I criticize him like this he is losing his spontaneity. He will have to find reality by himself. Reality which cannot be ‘interpreted’. There are facts that exist even when we don’t see them. The whole morning we did nothing but try to find this reality behind the notes. We never said: "You have to do it like this!" Instead: You have to discover what exists, beyond ourselves. I could explain to him: "The phrase is like this", and he would imitate Celibidache. – I insist that he himself finds out that he went beyond the notes without making them his own, without humanizing them.

What is the sense of a musical phrase? "Tata hee hoo hii doo pff" Why is this senseless? Because the beginning has no relation to the end. A sequence of tones follows a structure which finally connects the beginning with the end. When do I know that a piece has come to its end? I know it when the end is in the beginning. When the end keeps what the beginning promised. Continuity doesn't mean: to go from one moment to the next, but: after going through many moments to experience timelessness. That is where beginning and end live together: in the now. What is required to experience any structure as a whole? The absolute interrelation between the individual parts. When I don't feel the parts but the whole, what did my mind do? Integrate.

What did I learn from Furtwängler? One idea which opened all doors for my whole life and for all my studies: When the young Celibidache asked him: "Maestro, this transition in this Bruckner symphony – how fast is it? What do you beat there?" "What do you mean by ‘how fast’? he replied. It depends on what it sounds like! When it sounds rich and deep I get slower, when it sounds dry and brittle I have to get faster." He adjusts according to what he actually hears! According to the actual result, and not to a theory! "92 beats per minute." – What does ‘92’ mean in the Berlin Philharmonic, and what does it mean in Munich or in Vienna? What nonsense! Each concerthall, each piece and each movement has its individual tempo which represents a unique situation.

Something starts to move, but you don’t notice that it is moving in time. If anyone has the feeling it is either too long or too short, he is already out of the music. Here you can somehow live beyond time. In this sense music has no duration in time. In any normal concert you are out of it all the time. In a hundred concerts a year, if there are three where you somehow stayed with it – that would be a lot.

Releases

On DVD with Arthaus Musik:

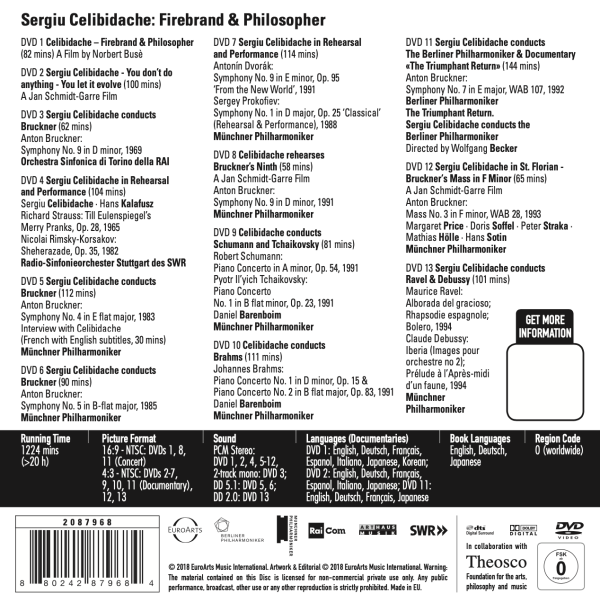

And in a 13 DVD box with EuroArts:

Texts

"Celibidache" – Interview

Sergiu Celibidache: On Musical Phenomenology

Sergiu Celibidache: Quotes

Celibidache’s Presence of Mind

Documents and Artefacts

Is a Celibidachian allowed to love Currentzis?

"Celibidache" – Interview

Jan Schmidt-Garre in conversation with Rebecca Fajnschnitt, June 1992

You worked on your Celibidache film for four years — during that time you could almost have completed an entire degree...

That’s how I felt about it. I knew that if I made this film, I would once again be close to Celibidache in a very different and very intense way. From the beginning, from the work on the outline, with which I had taken a lot of trouble — also in the sense of self-assurance — to the final cut, the four years were a degree with Celibidache for which I am very grateful.

So you already knew Celibidache when you were planning the film.

I knew him as a conductor, of course, and also had the good fortune to witness him in private, where he impressed me very much as a theoretician. I then went to his courses in Mainz, and in the beginning it was really mainly the aesthetics that fascinated me. I had studied philosophy and was eager to integrate Celibidache’s thoughts into a system, so to speak. I also tried at one point to get him to put it in writing, but he was very skeptical.

At that time, you weren’t thinking about the film at all?

Not at all, that came much later, out of conversations with friends.

And how did Celibidache react to that?

I was with him in Paris, but couldn’t bring myself to ask. Finally, after we had already had dinner together, I called him. "I would like to make a film about you." The answer came immediately and absolutely characteristically, "For me it’s of no interest — for you I’ll do it!" That’s how it was throughout the work: we had his basic yes to everything, but he wasn’t going to move a finger differently just because we happened to be standing there with the camera. That was incredibly exhausting, but it certainly adds to the authenticity of the film. One of the cameramen said now after the premiere, "it was an animal film." We were ambushing a tiger in the jungle and had to see that we caught the exciting moments halfway.

Were there also moments when you got so close to him that it became dangerous?

Only when we irritated him. Of course, we could not always be as invisible as Celibidache wished. Once in St. Florian, in the middle of a concert, during a very quiet passage, a cassette cover fell into the choir stalls. "Resurrectio mortuorum" clunk, clunk, clunk. Excellent acoustics. I avoided Celibidache’s gaze, otherwise I probably would never have dared to approach him again. When we went on anyway the next day, an orchestra attendant came with the message: Celibidache will not conduct until we have left the church. He wants to call the police. I thought, now it’s over. The F minor Mass in Bruckner’s church, above the sarcophagus — we had awakened a holy fury...

But it went on?

Amazingly enough. We even shot rehearsals again.

Did Celibidache see the finished film?

Yes, he said afterwards, " It’s not badly done. And what are you going to do with it now?" He didn’t react at all as a diva, as a concerned person, but absolutely professionally: a cinema spectator.

Do you think he expected a serious film to come out?

I don’t know. He had confidence in me personally, but I don’t think he saw the dimension it was taking on. After the first major shoot, I went to him to make it clear that this was not a hobby endeavor, and told him that the first hundred thousand marks had now been spent. Then he said, in his typical coquetry, "What, you have that much money?"

Whose money was it?

In the beginning there was no money at all, so the film school and friends stepped in. Then the film subsidies promised to help, but it can take eons for their money to actually flow. And finally, there was the German network ZDF. With all the institutions, it took courage to invest in the project: the outcome was quite open.

Did the film take the shape you had in mind?

It probably conveys what was important to me. However, I had imagined the form to be different, much more external, conceptual, formalistic. I thought of all kinds of creative means of structuring, of text panels, chapters, leitmotifs, and so on. Drawing board ideas. I’m glad now that the film was able to develop quite organically on the editing table and we didn’t force the material. There are a lot of roadside ditches. When I abandoned the strict didactic-conceptual model, I thought for a while that any explanatory ingredient on the part of the authors was harmful; I fell into a kind of cinema vérité ideology with slogans like, "We can do without commentary altogether." As if that were a value per se. I’m very happy with the hybrid form that has now emerged. Sometimes a short sentence off-screen works wonders and opens your eyes to a sequence in the first place. But the commentary must not, as the sound engineer rightly said, sit as a mother hen on the film.

Isn’t there a special challenge in a musical film to work musically with the film means, to correspond to the music?

I like corresponding, because I think the director has nothing to add to his subject matter and certainly not, as it can be so pseudo-intelligently put, to work "contrapuntally," "dialectically," so as not to "double" — a wonderful pseudo-problem of theater and opera direction. Yes, correspond, respond, that’s it. Working musically with film means, I’m skeptical about that. It would be a mistake to assume that a film about music can convey a musical experience — that’s not feasible. The subject matter is quite different. In concert, says Arnheim, I hear music; in film, I see musicians at work. This shift in emphasis must be made aesthetically fruitful. In other words, don’t cut apparently musically to the leading instrument in each case, to the wedding ring of the bassoonist, but follow a working action: Signs, looks, cues, notes, audience. The camera should not follow the music, but the making of music.

What are the focal points in terms of content?

Atmospherically important are the concert trips to Bucharest and Israel, and there is a dramatic document with Celibidache from 1950. But the center of the film is definitely the rehearsals with the Munich Philharmonic and with student ensembles — Bruckner’s Fourth and the Mass, Verdi’s "La forza," Beethoven’s Ninth — and the lessons in Mainz and at Celibidache’s mill in France. Celibidache conveys very basic insights, only sometimes in difficult terminology. I wanted to lead naturally to his important thoughts without scaring an untrained viewer with phenomenological terms like "reduction" or " recursivity". But also without starting instead with the sensation, with the "great outsider" who does not make records, does not jet from orchestra to orchestra, despises opera, conducts everything by heart, etc. Celibidache’s position should develop naturally, from its center, and not from the edge.

That was probably a plan that could only be realized in the editing room.

Yes, although of course the selection during shooting already decided a lot of things. What was very difficult but also very exciting in the editing room was the analysis of the material: boiling down fifty hours of film to units that you can work with, that you can assemble. The crazy thing is that you can’t shortcut this process, there is no "silver bullet." You have to peel off one onion skin at a time, from sixty minutes to thirty, to twelve, to eight, and then absolutely stop at the right moment: when the essence of the scene has taken shape and before it collapses into a mere gag. And then comes the synthesis: how do you group the themes, how do you create tension, how do you create an arc? After all, in the words of Celibidache, "the film cannot vibrate in its wholeness, it subdivides itself." Where are the joints?

You could apply Celibidache’s thoughts on musical progressions directly to montage?

Aesthetic insights are always applicable to all arts, even the para-art of filmmaking. In the film, Celibidache repeatedly speaks about the relation of beginning, climax and end, about the timelessness that occurs when beginning and end coincide in the work of art: eternity in the now. This applies, if it happens, to a Bruckner movement as well as to a poem by Matthias Claudius. And even if it can never be fully achieved in a documentary film, it remains a very strong guiding idea here as well.

Were you able to gain the necessary distance for your work at all from your personal knowledge and affection for Celibidache?

Why necessary? I have fought against this attitude from the very beginning. What kind of worldview is it to assume that the outside observer, as untouched as possible, dispassionate, sees more and more correctly and accurately? More "objectively"? It should be obvious that the one who loves a thing knows it better and understands it better than the one who first puts on the glasses of suspicion, so that he is not accused of falling for a charismatic. I don’t spend my time with someone I’m fundamentally suspicious of. But in journalism there is this idea that the suspicious dilettante is the best chronicler. What kind of disappointments must underlie such a view of the world, if I may be allowed to psychologize for a moment, that makes you think: Careful! better keep your distance for now. No, for me it was clear from the beginning that this perspective cannot do justice to Celibidache. What do I care about ulterior motives when someone has such exciting foreground motives? And besides, the great unmasking would also be terribly boring and could never carry a hundred minutes.

The pure hero worship can also be very boring ...

Perhaps there is a third. A friend wrote me after the premiere that he now believed that there could be an enlightened hagiography. A friend who, by the way, is critical of Celibidache. That made me very happy. But basically I wanted to go even further, namely completely away from the private person. Celibidache is a catalyst for me, a lens on art, and that interests me. I was made aware by one of my professors of C. S. Lewis, who used a beautiful metaphor to illustrate the turn of vision I’m talking about. He is standing in a tool shed and sees dust dancing in a sunbeam. He looks at the sunbeam: Looking at. And then he changes perspective and looks along the sunbeam to the outside of the doorway and sees the treetops, the sky, and the sun: Looking along. That’s what I was trying to do: Not to look at Celibidache, but with him at what moves him, the music, the laws of art. And my team members, who at first did not necessarily have a special approach to the subject matter and were only fascinated by Celibidache’s appearance, also made this turn of view in the course of time. That is what I would wish for every spectator. That he or she gets beyond fascination or, because of me, rejection and asks herself the question of truth: Isn’t the man right in what he says and does?

How was the cooperation with the musicians?

Celibidache’s students were very cooperative, as were the board and the directorate of the Munich Philharmonic, especially during the concert tours. The vocal soloists were also very accommodating. From the ensemble, at rehearsals in Munich, we were at least tolerated. More willingly by the choir than by the orchestra. A small additional spotlight over the top of a bass player was out of the question. Probably many musicians will be happy about the document now. Because the result is, of course, that choir and orchestra play leading roles in a Celibidache film. For him, making music together, listening to each other, is the center of artistic work. In the film, he must call out ten times: "Take over!" — that’s what it’s all about. This becomes clear most beautifully during a rehearsal for the Bruckner Mass, where Celibidache interrupts because the first violins have not listened to the solo flute. And then he says to Max Hecker, the flutist, my favorite phrase: "Maxi, breathe in much more calmly. I’m following you. We’re alone." In front of one hundred and twenty orchestra musicians, eighty men in the choir and a half-full hall: "We are alone!" It suddenly becomes clear that music is about people, about sym-phonics, about playing together. And that no metronome in the world will prevail against human, organic necessities.

Sergiu Celibidache: On Musical Phenomenology

“Expressive parts must be played more slowly than others."

Frescobaldi

“The harmonies of a presto movement must be kept very simple."

Haydn

“The length of a movement depends on the opposition of its ideas."

Schubert

Music and Sound

Music is not something that can be captured in a definition of thought concepts and linguistic conventions. It does not correspond to a perceivable form of existence. Music is not “something”. Something can become music under certain unique circumstances. This something is sound.

Sound and Tone

What do we know about sound, and ultimately about musical tone? Not much more than the prehistoric human being who, following an inner urge for freedom, found it through inspired search and borrowed it unknowingly from the universe. What is sound? Sound is movement. Sound is vibration. What moves? Material substance moves: a string, a mass of air or metal. We know that everything is movement. If sound is movement, what distinguishes sound – with the potential of becoming music – from other movements? Its own distinct fundamental structures are the same unchanging vibrations. The same number of vibrations over a certain unit of time: such is the nature of musical tone.

Tone and Man

This structure might exist in the world that surrounds human beings; however, it does not appear on the radar of his sensual watchtower. Man, who created the unchanging tone, delivered it from the inert depth of his material environment to the light of his consciousness, or one might say: brought it down from the divine stage. He stretches a length of elastic between two ends and makes it vibrate, blows into a bamboo tube or into a hollowed bone with holes; thereby he unwittingly creates conditions that allow him to transcend his original condition. Initially he is fascinated by the reliability of his discovery. Each time he creates the same conditions he makes the identical experience. His habitual volatile environment does not normally offer such experiences. He has come to know the transience of his environment and all he gets to see of it. The evenly vibrating tone is transient, too, yet for the duration of its existence manifests a permanent, recurring identity.

Overtones

The evenly vibrating tone does not vibrate alone. A host of overtones – not produced by the inventive originator – vibrate along with it and unite in an entirely new resonating multiplicity. Such overtones, which are directly dependent side effects, are immediately subsequent epiphenomena. These side effects displayed by the tone are nothing other than its different unequivocally structured stations on the way to its ultimate disappearance. We see ourselves confronted with the most fundamental phenomenon that gives the tone the opportunity to become music.

The Future of the Tone

The first overtone, the octave, appears later than the main tone, i.e. it is the main tone’s future. However, the octave is not something entirely new. Under melodic conditions it can appear new while being the same thing. The second overtone, the fifth, is entirely new and unmistakably different. It is the actual future of the key tone. In its relation to the main sound and to the other side effects it is overriding and thus inherits all prevalent attributes of the original tone. It is characterized by the Pythagorean relation of 2:3 that constitutes the smallest and the largest opposition of the first prime numbers. It stands in perpendicular position to the main function, which makes it the most stable sound interval. But despite its implied spatio-temporal structure, a tone alone cannot become music. Only the appearance of the next tone makes further dimensions of the expanding activity materialize, which works against the all-enveloping inertia, the all-devouring tendency to disappear.

Onepointedness

We will leave the material aspect aside now and focus on the nature of the human mind. The human mind is a self-contained, indivisible entity, constantly confronted with a multitude of phenomena; it is forever ready to appropriate and identify with what it perceived or to exclude what is impossible to correlate or reconcile. In Sanskrit this unique nature of the human mind is called Ekagrata. The English call it onepointedness: to be oriented towards one thing. It is the non-dualistic nature of our free consciousness. If the mind did not receive and again abandon what it appropriated, i.e. have the ability to transcend, there would be no further possibility for another appropriation. Instantaneous transcendence here and now allows the mind to regain its freedom. This freedom consists of the impartiality that is a sine qua non for the mind’s next appropriation experienced in correlation.

Reduction

The only possible achievement of our mind is its ability to integrate the differences, to eliminate duality of any kind. Consequently it needs to integrate all multiplicity in an evidently self-contained fact. The process of eliminating differences, of integrating all parts to an entity we call reduction. It is not a process of reconstruction, but of one-time and first-time new construction, dependent on one premise only: mutually complementing, internally complementary relationships between the parts or ways of being.

Transcendence

With mature sound perception individual phenomena disappear and the question arises: what remains? What remains is the relationship that can only be experienced through an act of transcendence. The transcending mind neither stays with the first nor the second part of a relationship, but it exceeds both of them and adopts the essence of their relationship. Do relationships disappear? They do. Not, however, like the tones from the physically perceivable sector whence they originate; instead they integrate into a novel, higher unity, which transcends the parts. This unity is the lasting work, the eternally possible function of the human mind.

Climax

Musical articulation always constitutes a process of expansion and compression. The right to persist in the spatio-temporal dimension – the right to continuance – is directly dependent on the opposition. To what point can the expansion extend? How far can the expansion stretch? To the point where it can expand no more. This crucial point of all expansive development is called climax. This turning point where the extroverted direction of the expansion tips over into an introverted one is the most cardinal pivot about which every form of musical architecture is functionally structured. Everything that happens in the expansive phase goes through organic complementing in the compressive phase, which furthers the reduction process. If this is not the case, the end is not the consequential, inevitable result of the beginning. If, however, the end is the result of the beginning, it is simultaneously present with the beginning, as in the act of thinking. Both the act of thinking and the musical act manifest and materialise in the spatio-temporal continuum. But in terms of their essence they stand beyond time, simultaneous.

From a lecture held at the University of Munich on 21 June, 1985

Sergiu Celibidache: Quotes

You can’t do anything other than let it happen. You just let it evolve. You don’t do anything yourself. All you do is make sure that nothing disturbs this wonderful creation in any way. You are extremely active and at the same time extremely passive. You don’t do anything; you just let it evolve.

A rehearsal is not music. A rehearsal is the sum of uncountable ‘nos’. ‘Not too far, not too loud, not above the bassoon, not so dull.’ How many ‘nos’ are there? Billions. And how many ‘yeses’? Just one.

That is the complete training. You have to do at your seats what I am doing at mine. You have to conduct with me. We react spontaneously to what we hear, that is, functionally, as is necessary. Not "this is marked piano, this is marked forte…" – no one is interested in that.

I don’t know if that gives you an idea of what I would like: to emanate from what already exists. The way oil spreads, becoming wider and wider and wider. Not so pointed. Those are notes, but not yet music.

What is the "interpretation" in what we are doing here? It’s nothing else but finding out what the composer had in mind. He starts from an experience and looks for the notes. We start with the notes to come to his experience.

When I criticize him like this he is losing his spontaneity. He will have to find reality by himself. Reality which cannot be ‘interpreted’. There are facts that exist even when we don’t see them. The whole morning we did nothing but try to find this reality behind the notes. We never said: "You have to do it like this!" Instead: You have to discover what exists, beyond ourselves. I could explain to him: "The phrase is like this", and he would imitate Celibidache. – I insist that he himself finds out that he went beyond the notes without making them his own, without humanizing them.

What is the sense of a musical phrase? "Tata hee hoo hii doo pff." Why is this senseless? Because the beginning has no relation to the end. A sequence of tones follows a structure which finally connects the beginning with the end. When do I know that a piece has come to its end? I know it when the end is in the beginning. When the end keeps what the beginning promised. Continuity doesn’t mean: to go from one moment to the next, but: after going through many moments to experience timelessness. That is where beginning and end live together: in the now. What is required to experience any structure as a whole? The absolute interrelation between the individual parts. When I don’t feel the parts but the whole, what did my mind do? Integrate.

What did I learn from Furtwängler? One idea which opened all doors for my whole life and for all my studies: When the young Celibidache asked him: "Maestro, this transition in this Bruckner symphony – how fast is it? What do you beat there?" "What do you mean by 'how fast'? he replied. It depends on what it sounds like! When it sounds rich and deep I get slower, when it sounds dry and brittle I have to get faster." He adjusts according to what he actually hears! According to the actual result, and not to a theory! "92 beats per minute." – What does ‘92’ mean in the Berlin Philharmonic, and what does it mean in Munich or in Vienna? What nonsense! Each concerthall, each piece and each movement has its individual tempo which represents a unique situation.

Something starts to move, but you don’t notice that it is moving in time. If anyone has the feeling it is either too long or too short, he is already out of the music. Here you can somehow live beyond time. In this sense music has no duration in time. In any normal concert you are out of it all the time. In a hundred concerts a year, if there are three where you somehow stayed with it – that would be a lot.

Celibidache’s Presence of Mind

Obituary by Jan Schmidt-Garre, first published in Die Wochenpost, 17.8.1996

German version on waahr.de

No one brought so little baggage on to the platform. He did not even have his baton with him – it was left on the leader’s desk by the orchestra assistant. And of course he did not carry a score with him either – except in his head. And even there he did not perceive it as baggage, as a burden from the past which he brought to the concert with him, but as what he needed to exercise his best talent: his presence of mind. We learned as his students through molecular exercises that this paradox is possible: it is possible to internalize a score, it is not a lifeless entity in the memory but a living structure. He would ask someone to write a random 12-tone row on the blackboard, the most desolate phrase that one could imagine. And then the process of humanization began, the search for its innate order. How is it divided? How can it be phrased? How can it be conducted? Where are its joints? One student after another would go to the piano and try his luck. Celibidache could be cutting and sarcastic if you didn’t have it right; he could be a disheartening teacher. Finally someone would succeed, and suddenly this lifeless, amorphous material sprang to life and assumed shape. And then during the break on the giant stairs of the University of Mainz, the stairs that the fragile maestro mounted every morning, I suddenly found myself whistling something as easily as if it were by Schubert: the 12-tone row.

The rehearsal begins. The cellos and basses play the first phrase of the Kyrie from Bruckner’s Mass in F Minor; the violas take over, then the violins. A giant, giant body begins to take shape, infinitely larger than the 12-tone row, but structurally similar, just as rounded and closed. And then all of a sudden: "No! That’s mambo!" The violins were a little blurred just before entry of the chorus. Celibidache’s disappointed face has looked up at me a hundred times from the editing table, with its pain at the impairment of a well-formed shape, wounding the very man who has keenly perceived and mentally projected this shape. This inaccessible, solitary emperor had the gift of giving himself completely to the vibrant, living sonorities. The man who did not care if he was loved or liked by all, who maintained a distance even in laughter, this man was completely naked, exposed and infinitely vulnerable at the podium. And the results were accordingly bounteous when everything was right. The music emanated from a giant personality capable of opening a vast number of sluit gates. His Zen ideal of opening and emptying himself to the music was misunderstood by many students as a state of poverty, thin-blooded and lacking in substance, but no: this colossus opened himself up – when it worked, that is to say two or three times in a hundred concerts, as he used to say – and let us participate in a huge surge of energy.

"What is your name? Do you smoke? Never touch a cigarette!" That was the initiation for countless students from throughout the world when he taught – gratuitously a rule. Maybe he also said, "you have to live with me for a few years", and then you were under his spell. From then on life was divided into right and wrong. His personality was oppressive for many, and he was never reserved in that respect. Skeptics often described him as a guru, and there were certain parallels that we his students couldn’t deny. But is it possible for someone with vision, a true spiritual master, to be reserved?

Celibidache’s rehearsals were never hypothetical; every rehearsal was the real thing, presenting the greatest possible challenge to each musician to submerse himself in every piece as if for the first time, to be driven on by what had been heard and experienced. All or nothing: as long as he didn’t interrupt, everything was fine. It wasn’t the little inaccuracies that made him stop, but breaks in the flow of music, for example, in the Benedictus of the Mass in F Minor, if the violins didn’t listen to the flute solo, didn’t pick up its phrasing. Celibidache angrily corrected the violins and then gently turned to the flutes: "Maxi, breathe in much more calmly. We are alone." The flutist should follow the organic flow of his breathing, the human scale. We are alone? Two human beings make music with one another, listen to one another, jointly give shape to a work of art, unaffected by the external demands of a metronome. But physically, too, they are alone: two hundred colleagues in orchestra and choir are obliterated in this intimate moment shared by flute and conductor. Celibidache could command such intimacy anywhere, at anytime.

It was his presence of mind that rewarded him with such a long life, that gave him renewed life and energy for new rehearsals and concerts after every illness. Once on the platform there were no worries about the next diagnosis, no fears about the coming night – here there was only the pure moment, which he was never ready "to sacrifice to the future" (to quote Horkheimer): the sound here and now. The mystic "instant". In a completely unsentimental, objective sense, making music was a religious act for Celibidache. No baggage, no memories, no outwitting transitoriness with gramophone records – he could and would not rest on anything: each rehearsal was a clean state, always new, always claiming the whole person. In this way he embodied the ideal of the conductor and artist and human being with a radicalism shared by few in the 20th century: to live in the present.

(Jan Schmidt-Garre studied with Celibidache before shooting his film "Celibidache – You Don't Do Anything – You Let it Evolve". Celibidache died in 1996.)

Documents and Artefacts

Presented at the IMZ and EBU workshop "On Making Documentaries about Music and Musicians"

by Jan Schmidt-Garre

We have been talking a great deal about music today and about the right way of staging music or musicians in a documentary. The word indicates that we are concerned here with documents, and I would like to develop a few thoughts on this subject: on the relationship between reality, depiction, and fiction, between the document and the artefact.

1. Document

The presence of the camera changes the object. Light, framing, camera movements, and later the selection and context rob the document of its innocence and convert it into an artefact that is determined by the medium and the author at least as much as by actual reality. "The medium is the message", as Marshall MacLuhan said. Is the pure, innocent document a fiction?

Example 1: Callas/Habanera

Sometimes, however, the message is the message. This single shot contains everything: musical theatre, the art of singing, identification, distance, irony, devotion. The power of this document protects it from being devoured by the voracious medium. Direct cinema. Cinéma vérité. This ideal may be naïve in terms of epistemology, but it is attainable in rare and fortunate cases, and it was with it that I approached my first major subject as a film-maker, the conductor Sergiu Celibidache. I accompanied him for three years to rehearsals, on concert tours, and to watch him teaching. How could the pictures we took of Celibidache achieve the directness and authenticity of the pure document? "It was an animal film", the cameraman said when filming was finished, and indeed we had lain in wait for a tiger in the jungle. Celibidache did not seem to notice we were there, and his vital self-confidence prevented him from changing by one iota from his normal self when the cameras were running. And the musicians who were playing under his baton were so much enthralled and challenged by his authority, that questions of shame or vanity simply never arose.

Example 2: Celibidache/Forza del destino

However, it is possible for a crack to appear in the self-contained system of Cinéma vérité if reality fails to stick to the agreement, which is: we observe you and you don't notice us. If the document suddenly looks at me, it catches me red-handed as a voyeur. It turns my own weapons against me and forces me into an uncomfortable intimacy, an intimacy that I had not asked for. Suddenly a window opens onto the actual reality behind that which is being depicted.

Example 3: Celibidache/Forza del destino/Glance into the camera

2. Artefact

My film "Bruckner’s Decision" also started as a documentary. A brief episode in Bruckner’s life had caught my interest, a time of crisis and transition. He had been sent to a water spa in 1867 on account of psychological problems. He spends the summer there and finally, at the age of 43, takes the existential decision to become a composer. Everything that follows flows from the decisiveness he has at last gained: his move to Vienna, his position as a professor of composition, and most particularly his powerful Masses and symphonies. I could not draw on any documentary film material from 1867 so I decided to use what is now called "dramatic reconstruction", and created my own artefacts. In the sound I combine these artefacts with authentic documents from Bruckner – letters –, and I complement and reflect them with letters from a fictitious person whom he meets at the spa – another artefact.

Example 4: Bruckner’s Decision/Bad Kreuzen

The film met with approval and objections, but there was one accusation that was never made, and for me this is the greatest compliment of all: my film was never accused of falling to pieces, of trying to combine too many disparate elements. In addition to the artefacts from Bruckner’s spa treatment there is also documentary material in it of a present-day Bavarian Corpus Christi procession, modern church-goers leaving after the service, Bruckner as a child in St. Florian, clouds, photographs from Mexico in the 1930s, and a painting by Manet. Bringing these heterogeneous elements together into one consistent whole was in my view the challenge of the editing-room, and it was here, as with all my films, that the creative work actually took place. The experience I have had of artists like Bruckner and Celibidache, and his teacher Furtwängler (about whom I am currently making a film essay), is constantly challenging me to look for a self-contained form in art, an art that does not naively avoid, let alone deny, the ugly, the disturbing, the destructive, but attempts to integrate it into a coherent whole. I defend this principle against the over-powerful tendency of our day to present a torso, a fragment, an open form. Every cut that I make in the editing-room is an attempt to re-create the innocence – reconstruction in the age of deconstruction. In the editing-room we played around with our artefacts and tried out different combinations, and suddenly, again, a window opened. Two shots that we had filmed independently of one another revealed themselves as a straight shot and its reverse angle. We see what Bruckner is seeing. We see with his eyes, we are suddenly inside his head. This creates identification and empathy. And that is how "Bruckner's Decision" turned into a feature film.

Example 5: Bruckner’s decision/glances

3. Artefacts from documents

"Belcanto" is a series about historic tenors, and came about not only because of my enthusiasm for these magnificent musicians but also because there are exciting documents available on the great singers from the early days of sound films that hardly anyone knows anymore these days. These documents are not immediately accessible; there is a layer of cultural dust on them that we first had to remove. This starts with the technical parameters; finding the original negatives from which we can make a tele-cine transfer and define the best possible framing, avoiding the cut-off heads, and finding the right running speeds – which can be anywhere between 18 and 24 frames per second – as this can after all affect not just the pitch but also the colour of the voice. However, more than this was at stake: we had to bring historical material to life. The old film documents had to be integrated as perfectly smoothly as if we had staged them today specially for our portraits. The material we were filming now, on the other hand – the atmospheric scenes and interviews with experts and eye witnesses, and so on – had to be brought close to the historical documents. So we filmed in black-and-white. We tried to bring all the components together into a flow of film. Historic locations such as the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires or the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth were not filmed as dead pieces of architecture but as the backdrop to real live scenes. Photographs are not cut in as lifeless stills, but they appear in the hands of the people we are talking to, again, as parts of a scene being shot today. Symptoms of the past that you can analyse and categorise with polite interest turn into symbols that lead to an understanding and experience here and now, to real empathy. Staged situations for bringing historical material to life: artefacts from documents.

Example 6: Caruso/Little Italy

In "Belcanto" we worked to a strict pattern. We were involved in a 13-part series, so we had to take care of recognisability, of a clear graphic profile, and so on. At the same time, however, we tried not to lose sight of the need for just a little irritation, for those windows in the television screen or on the cinema screen through which actual reality flashes at occasional moments. We tried once again to create structures that were so stable that they could even still carry the moments of disparity without assimilating them in a "kitschy" way. There was such a moment in Ireland, in a meeting with the John McCormack Society. Elderly McCormack fans meet every Thursday for no other purpose than to listen to records together.

Example 7: McCormack/Society

The devoted glance of this lady, in my view, brings John McCormack, who died 57 years ago, back to life: his patriotism as an Irishman and his faith; but at the same time it shows what he still means to Irish people today – and how long ago it all is. But in return for that this shot has to be maintained for such an embarrassingly long time.

4. Documents from artefacts

Celibidache's glance into the camera had opened a window into the reality behind the documents of Cinéma vérité. This is, because a totally different picture is seen from the Divine point of view from the one we were filming: musicians with instruments and the conductor in front of them, yes, but also: spotlights, cables stuck together with tape, microphones, rails, cameras, technicians with headphones. Revealing this situation as it actually exists is the principle behind my film "Opera Fanatic".

Example 8: Monty Python/a film within a film

The idea behind "Opera Fanatic" came from outside: Stefan Zucker, a brillant New York opera expert and singer claiming to be listed in the Guinness Book of Records as the world’s highest tenor, was planning to go to Italy and interview the great female singers of the 1950s and 1960s. He asked me if I would like to join in. In order to get a clear picture of a project I like to place myself in the role of a doctor and break the development process down into the three phases of anamnesis, diagnosis, and therapy. The anamnesis starts with the initial idea: a subject, material, or as in this case a suggestion from outside. I start researching and building up a personal relationship with the material. Here, that consisted of listening to records of the singers, studying their biographies, their repertoires, and so on. This leads to the diagnosis. I try to recognise the material as such, to take hold of it. What kind of a project is this? Actually, in this case the interviews with the old ladies were actually only secondary; the real subject of the film was Stefan’s journey through Italy, his search for the great pathos of a long-vanished opera, his search for childhood memories, and perhaps even the search for his own mother, herself an opera singer of those days, who used to take him with her when she made guest appearances in Italy. Once the material has been diagnosed the therapy can start: how can this be realised in an adequate way? I decided to locate the film on two levels: Stefan’s travels through Italy in an old van, with all his expectations and comments, filmed with a hand-held camera on Super 16 mm, and in parallel with that the interviews with conventional lighting, the camera on a stand, shot on video. A film within a film, documents from artefacts.

Example 9: Opera Fanatic/Gencer

The only "true" side of the interview situation in Cinéma vérité terms is the interview situation itself, with all the cables, artificiality, and nervousness. How will Giulietta Simionato, whose apartment we have turned upside-down, react to Stefan Zucker, who is all a bit of a mystery to her and now asks her, in his castrato voice and affected Italian: "Let us assume we are in the 1930s and you are at the beginning of your career. What would you do different?" We see her sitting all amongst the cables and lamps, we see Stefan Zucker, the sound engineer, the video-cameraman, and we see the video-camera waiting for the answer. She needs a few seconds, and then: "I wouldn't do it again."

Example 10: Opera Fanatic/Simionato

This sentence, in this situation and after this pause for thought, comes fairly close to the ideal of the directness and authenticity of Cinéma vérité. But even here, again, it is not Giulietta Simionato as such who is speaking. There is no key-hole through which we can see her. But there is the actual Giulietta Simionato, here and now, in this situation, with this face that she is showing to us. And in order to understand this face I open the context out as wide as it will go and thus try to reach the limits of the observation situation. I unmask the documentary situation of the interview by documentary means as artificial: documents from artefacts. However, even in "Opera Fanatic", which so to speak institutionalises the open window and turns it into a principle, there is a moment when reality breaks in and bursts out of the framework of the film.

Example 11: Opera Fanatic/Pobbe

Is Marcella Pobbe being compromised here? Is Stefan Zucker being compromised? The question is connected to my subject because a document that is created without the knowledge of its protagonists has, in the nature of things, a greater potential for authenticity – if only of a somewhat negative kind. Every viewer will answer for himself the question as to whether "Opera Fanatic" exposes its heroes. I can only try to explain my attitude to those scurrilous, weird phenomena that keep turning up in my films. My attitude is determined by empathy and identification, and at the same time a sense of distance. This may sound like a paradox, and perhaps even perverse, but as I hope the films show it is possible. I like Stefan Zucker but at the same time I recognise very clearly what an impudence this man is. I identify myself with his obsessions, but that does not mean that they become mine. I never laugh at anyone but I welcome and provoke laughter. I think this attitude is camp. Camp is not ironic and not cynical; it is a broken and desperate yearning for authenticity that sometimes can only be achieved in this kind of strange indirect way.

5. The document recovered

Example 12: Monty Python/a film within a film within a film

Just as the tortoise kept ahead of the hare, reality always seems to be a step ahead of us. Not even exposing the observation situation releases us from this dilemma. There is always an irreducible rest left over, a "strange loop". A thousand veils, and no reality behind them as Lyotard says? There is one escape route, and this is art: somehow the absolute artefact. To put it in the words of the Romantics, "All one can actually do is write poetry – everything else is inexact." And the absolute document?

Let’s go back into the editing-room, whith the cans that came out of three years’ filming Celibidache. Here the trilogy of anamnesis – diagnosis – therapy is repeated. The first step is to gain the full acquaintance of the material, to assume ownership over it, to master it – this is the most laborious and unproductive part of film-making. I keep trying to shorten it, or delegate it to someone else, but it doesn’t work; the author himself, like a good doctor, has to go through this whole process. In the diagnosis the material is then recognised and evaluated: where in this unstructured continuum does a take start and end? What kind of a character does it have? Does it belong to the exposition? Or to the resolution? What is the inner dynamic of my material? The only virtues that help here are honesty – the material must be recognised and accepted for that which it is – and humility: I must not demand too much of the material, or force anything onto it of which it is not capable. I can and must work with that which is given, and not with unrealised intensions or prefabricated theories, I must not overrule or misuse my material. "Going on from the given" is Celibidache's definition of the legato, and for Furtwängler the highest aim for any musician is real legato playing. Interpretation, regardless of whether it is of musical or film documentary material, would then mean: recognising and realising the forces resident in the material. Just as good therapy can only be the kind that helps the body to heal itself. Each detail thus finds its position out of itself, and the film in its entirety takes on the force and necessity of an organically grown structure. Our document, having lost its virginity during the course of this long story of voyeurism, manipulation, and corruption, can regain a second innocence. The film then no longer needs any window onto actual reality because it has become a window itself, the icon through which reality reveals itself. Just as in Zen: "When we reach the ground and the origin, the mountain is once again a mountain and the river once again a river, the meadow is green and the flower is red."

Is a Celibidachian allowed to love Currentzis?

by Jan Schmidt-Garre, first published in Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, 20.8.2017

(German version on waahr.de)

„How was the super crazy Currentzis?“ my friend Christoph asked by e-mail. I had told him that I was going to the premiere of Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito at the Salzburg Festival, conducted by Teodor Currentzis. I hesitated to answer. The fact that I had liked it was kind of embarrassing, especially in front of Christoph. We had both studied with the conductor Sergiu Celibidache, Christoph much more intensively than I did, but I had also become very close to Celibidache because I had made a film about him over almost four years. And I knew, of course, what Celibidache would have shouted in that Titus, every few bars, „Locally thought!“ That was one of the worst judgments. It meant that the musicians had celebrated a beautiful passage without putting it in the context of the whole – and context was all that mattered. Then in the evening I gave myself a jolt. One does have a duty to confess, I thought, and wrote Christoph briefly, „It was great!“

To entrust Currentzis, of all people, with his first opera premiere was a real coup for the new artistic director of the Salzburg Festival, Markus Hinterhäuser, a manifesto. And he engaged Currentzis not with the Vienna Philharmonic, the Festival’s traditional orchestra, but with the Russian orchestra MusicAeterna, which Currentzis had founded thirteen years ago in Novosibirsk as a baroque ensemble and then developed into a major symphony orchestra in the city of Perm. The recordings of Mozart’s Figaro, Così and Don Giovanni that made Currentzis famous in the West were produced in the Perm Opera House. With the Salzburg premiere, he has now arrived in the „royal class,“ as the German newspaper Weltwrote; for Süddeutsche Zeitung, he is currently „radically the best Mozart conductor.“

Why did I find it so difficult to judge, why couldn’t I just write down a superlative, why the dramatic talk of confession? Because the way Currentzis makes music is not only a little different from what Celibidache did, because he does not only play a little faster, sharper, rougher, like many conductors today, but because a paradigm shift is taking place here. In the old paradigm, for which Celibidache is not the only one, of course, but, well: paradigmatic, the unity of the artistic form was the highest goal. A musical phrase is heard, the next one answers it, the proceedings open up again, and again there is a response. One plus one becomes two, two plus two becomes four, and so on until the climax, after which the forces reverse and return to the calm of the beginning, so that the whole process is but a single reaching out and catching up again, a single movement of expansion and compression, a single breath that can extend – say in the slow movement of Bruckner’s Eighth – over an incredible thirty-five minutes. Viewed from the outside, as Celibidache would immediately object, because from the inside, from the experience, there is no temporal duration, all this happens in the now. What Celibidache expressed in the seductive image that the end is already contained in the beginning.

For Celibidache, as for his teacher Furtwängler, this idea was indissolubly linked to tonality. „On the firm foundations of the triad,“ Furtwängler wrote, „the cadence arises in tonal music. Out of the release of tension the tension grows to grasp the multiformity of life and finally – according to the law according to which it started – to return to the starting point, to the so-called tonic. Every great piece of tonal music, therefore, despite all the excitement that can be driven to the limit of human comprehension, exudes a deep and unshakeable tranquillity that permeates everything and everyone like a memory of the majesty of God.“

Now, what does Titus sound like with Currentzis? Rugged, wild, archaic. Utterly strange and new. On a small scale, of course, the complementary phrases also exist with him; a musical person cannot help but feel complementary in this way. But then suddenly there are contrasts of a harshness that can no longer be resolved with the available musical material. Dynamic contrasts from the most extreme pianissimo I have ever heard to the strongest fortissimo. Entrancing caesurae in which the world holds its breath, but also abysses in which it loses itself.

„At the hand of the atonal musician,“ says Furtwängler, and one thinks he is talking about the Salzburg Titus, „one walks as through a dense forest. Along the path, weird and wonderful flowers and plants draw our attention and one does not know oneself where one has come from or where one is going. The listener is gripped by the feeling of being exposed to the power of elemental existence.“ Seventy years ago, Furtwängler was already well aware of the fascination that could emanate from this strange world: „There is admittedly no denying that a certain note has thus been struck in the modern man’s feeling for life.”

According to Thomas S. Kuhn, a new scientific paradigm emerges when the old one is in crisis. Anomalies occur that can only be explained in a makeshift way, and finally, somewhere in the world, „extraordinary research“ begins that leads to the new paradigm. Talk of the crisis of classical music began around the time of Furtwängler’s death, in the 1950s. Today, the average intellectual no longer considers it a lack of education not to know what a liberating experience a coda can be, in which the composer, on the last bars of the piece, with dwindling strength, gains some more time, through small unassuming motions in the musical material. And while the intellectual would be uncomfortable not being able to say anything about the golden ratio or about the form of the sonnet, he does not know how the dominant relates to the tonic – and what that sounds like.

When Teodor Currentzis works out the works of Mozart, Rameau, Tchaikovsky or Shostakovich with a group of friends in the foothills of the Urals, with no time constraints, no obligation to perform, no financial pressure, this can certainly be called „extraordinary research. « » You can’t gather partisans in the capital,“ Currentzis says, „you gather them in other places, somewhere in the woods.“ The new paradigm that emerged from this underground is now conquering the world from Salzburg.

And Currentzis himself is very aware that this is a new paradigm. „Every person,“ he says, „has a Dionysian and an Apollonian side. Classical music has dealt only with the second. The Dionysian is the wild, unadorned side of the subconscious, where its own algebra and geometry rule. It leads to drunkenness and ecstasy when it comes into contact with the outer world. When was the last time you experienced Dionysian ecstasy in a concert hall?“

The musicians of the Apollonian paradigm wanted to convince. Currentzis wants to persuade and overwhelm. To this end, he is willing to use any means, including extra-musical ones. At the beginning of his concerts with the phenomenal MusicAeterna Choir, he completely darkens the hall. A distant chant rises from nowhere. It brightens a bit, and the black-clad Currentzis slowly strides to the podium and takes over. At the end of the intermission of Titus, he mingles with the choir singers and lays flowers of mourning on the stage for the shot emperor Tito. For him, theater and music are one, and significantly, in Titus it is the accompagnati that are particularly gripping: the most impure music of the opera, the recitatives with orchestra, completely committed to action and emotional dynamics, close to stage music – and far from the closed form.

Much is lost, and perhaps one must have inhaled the old paradigm as strongly as Christoph and I did under Celibidache’s influence to feel the farewell so painfully. But a very great deal is also gained: a radically contemporary world that makes one wide awake and drunk at the same time. Currentzis reaches the „modern man“ of whom Furtwängler spoke more directly than almost any other musician today. In 2005, then still in Novosibirsk, English critic Peter Culshaw asked him if he had a mission. „I will save classical music. Give me ten years, and you’ll see!“