Gubaidulina: 2nd Violin Concerto

Facts

Concert Film, 40 min, 2008Directed by Jan Schmidt-Garre

In August 2007, Anne-Sophie Mutter performed the world premiere of Sofia Gubaidulina’s 2nd violin concerto in Lucerne with conductor Simon Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic. This piece by the Russian composer (born in 1931) was an important event in many respects.

Sofia Gubaidulina’s international breakthrough came in 1980 with her first violin concerto, Offertorium. To this day, it remains her most often performed piece. In spite of all the other pieces she has written in the meantime, it is her second violin concerto that violinists, conductors and orchestras around the world have eagerly been awaiting, especially since she was commissioned to write it in 1992 by Paul Sacher, the Basel conductor and patron of the arts. It was his wish that Gubaidulina’s new violin concerto first be performed by Anne-Sophie Mutter. Fifteen years later, that dream finally came true.

Featuring:

Anne-Sophie Mutter

Sir Simon Rattle

The Berlin Philharmonic

Cinematography: Thomas Bresinsky

Editor: Gaby Kull-Neujahr

In co-production with SF

Texts

Sofia Gubaidulina in Conversation with Jan Schmidt-Garre

The conversation took place one year prior to the world premiere of Gubaidulina’s second violin concerto, performed by Anne-Sophie Mutter.

German version on waahr.de

I am fascinated by the name „Anne-Sophie Mutter”, and by the figure of Sophia altogether. She is alongside me throughout this period of composition, because it is the soloist’s name...

And your name, too.

Yes, I am also Sofia. It struck me that I am Sofia and she is Anne-Sophie. This is where the figure of Sophia, the divine aspect, comes in. Perhaps the work will turn out to be a self-portrait. Perhaps – I haven’t finished it yet. Sophia is a mysterious figure of great significance worldwide. She was born to the ancient Greeks, although there she was a fairly abstract figure. For me, she becomes more personal in the Old Testament. And she is of great importance to the Russian people. According to some scholars Sophia came as a defender and protector to the baptism of Russia.

So in your opinion Sophia personifies more than just wisdom?

She personifies wisdom and also the female aspect of God; the creative principle of divine existence. God contemplates his own perfection, but that is not enough. He must realise this perfection and Sophia is the initiator of the world; her power, the power of Sophia, must be regarded as a creative act. She is not a god, goddess or angel. She is the creative principle. And for a work of music it is very fitting to portray this creative principle as fate. I don’t believe, however, that I’m composing something of concrete content. Nevertheless, I have before me, an intimation, a metaphorical suggestion, of this countenance.

You mean the creative principle itself becomes the theme of the composition?

The musical theme and its inversion, for example, may be considered the ambivalent forces Sophia symbolises. Why ambivalent? Because she appears as the female aspect with respect to God; but then she enters the world, she creates and protects the world as the male aspect. Countless profound thoughts have been expressed on this subject. The problem of unity and multiplicity for instance – a very important philosophical problem. Sophia appears as the female aspect in order to generate multiplicity, the world in multiplicity. In the world itself she strives to return to God, to unity, and this is precisely the artistic problem: every work that we compose represents this transition from unity to multiplicity – musical form – and back again to unity, the word of God. This is the meaning of the work of art.

Does the unity to which it returns constitute the coherence of the work?

Yes. The work as a whole grows into unity. The culmination, the artistic edifice, appears in our memory as something whole and unified, but it is preceded by the form that leads to this unity. And it is Sophia who creates this process.

When you work, does the idea of the whole already exist or are there first individual segments that you unite in the course of the process?

First I hear the end of the piece. After that I return to the beginning. It is difficult to tell in what order it happens. It varies completely because it happens too intuitively. On an intellectual level this is difficult to grasp and recall. In any case, I have noticed that I begin each work in reverse order, starting not from the beginning, but from the end. I hear the end, or something close to the end, and the sound is all mixed up and difficult to identify.

You make it sound as if the work is there already in some form of reality and that the only thing left for you to do is to bring it down to earth.

The form of the work does not seem like a form at first. It is without the time component, it stands apart from time. Thus it is not the work itself. I cannot say that I hear the work as a whole at this point, but it is all there bundled up and much too complicated. I cannot write it down, this moment. I first have to clarify and clarify before I am gradually able to arrive at what I heard originally.

Mozart describes just this in one of his letters. Perhaps you are familiar with it? He says that what is most beautiful is when the work comes together, all at once, in one moment.*

Maybe he heard it as a form, in detail. I assume that is what he means. He even describes details that he heard. I cannot say that I hear details. I hear a chord so tremendously complicated that I cannot immediately write down the details. It is a mysterious chord. And then, eventually, I get closer and closer to it. But in my experience there has never been a melody at the outset that has gradually developed... I have never experienced that.

Do you always manage to pin down this image, to capture what you heard at the very beginning?

It mutates. This chord mutates. I can never quite approach this chord. It is too complicated. Besides, this original chord from which everything derives is beyond the capacities of my instruments, my voices. There are notes in this chord that are too high, for example; none of these sounds are available to me in the orchestra. So I have to compromise. Then comes the mechanical work, and here I know what is possible and what is not. So I only write notes that are available to me in the orchestra and in human voices. So there is a discrepancy between reality and what I heard in the very beginning. The two do not correspond.

What point are you at with the piece now?

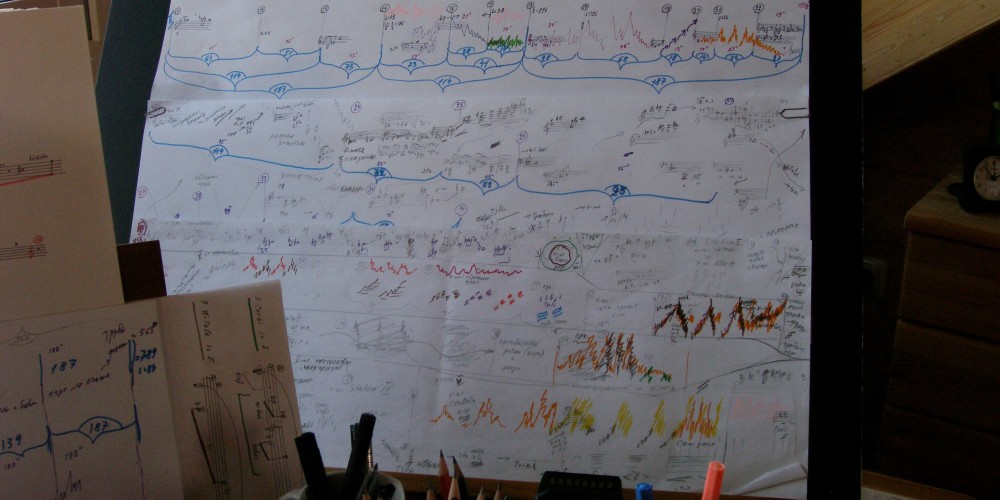

First I always put things down in the black, making sure that everything is there. Then I need to hear the whole thing again and again – listening over and over and experimenting precisely using the metronome.

What do you mean by "in the black"?

What is very important for me are these fast moves. I find it disadvantageous to write neatly as I compose, because my intuition suffers the moment I think about the cleanness. Writing in the black means I can write very fast, it’s almost like sketching. It is the score, but not a clean copy. It takes two rounds of work. It may not be efficient, but it is very important for me. First I have everything in the black, then I listen to it as if I were the soloist so as to ensure that everything is comfortable for the soloist and for the conductor... I listen as if I were the flautist, the bassoonist, as if I were playing the French horn. After working in the black like this, I take on the role of performer; only then do I transform my score into a white version.

Is there a design phase prior to this black process?

Yes. I work a lot on the architecture of the piece. The form plays the principal role for me, the construction elements in particular, even though I am actually a rather intuitive person and consider intuition to be crucial in creative matters. But for art this is not enough.

I see that you own a large collection of mathematical books, one on symmetry, for example. Does this influence your work?

I place a great deal of value on mathematical series such as the Fibonacci series, for example, and its derivatives. This problematic is very important to me. In this composition I use the numbers of the Bach series. At the centre of the Bach series stands the number 9, not 0, as in the Fibonacci series. I find it fascinating that I have a centre here and that 23 and 32 are symmetrical.

If you often work to such plans, do you stick to them throughout the process?

It varies. Sometimes I manage to implement the plan, sometimes I don’t. The thing is that I work intuitively rather than intellectually, and you really need to be connected to these systems. When I don’t succeed, I let go of the numbers and pursue only the intuitive approach.

So it serves you as a map for your intuition, provides you with a starting direction?

Working exclusively through intuition is not beneficial to art. One is prone to all kinds of fantasies and that is too materialistic. Pieces that are written solely intuitively, leave me rather dissatisfied. On the other hand, I’m left feeling entirely satisfied by the works of Johann Sebastian Bach, which contain both: those mathematical principles and the fiery stream of intuition.

* „The thing is indeed almost finished in my head, long as it may be, so that I am able to behold it in my mind with one look as though it were a beautiful picture or a handsome person, and so that I don’t hear it in my imagination in its intended chronological order, but all at once, as it were. That is a feast! From now on, all searching and making in me happens as in an intense and beautiful dream. But this over-hearing, all at once, is the best thing of all.” (From a letter attributed to Mozart)